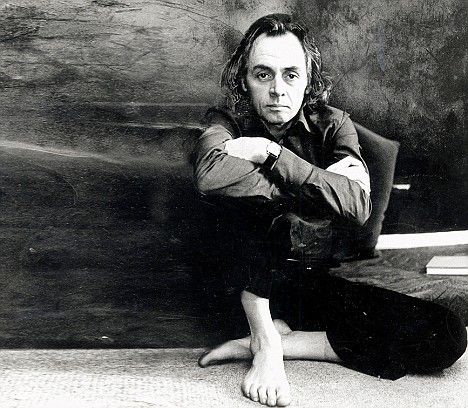

R.D. (“Ronnie”) Laing and Me, 1972

by Phyllis Chesler

Some time ago, I was asked to contribute to a volume about the late British psychiatrist, R.D. Laing. At the height of his fame, he visited New York City and asked to meet with me. I considered it quite an honor.

“CONVERSATION IN TWO BEDS.”

When R.D. Laing (“Ronnie”) came to America, he asked that we meet. I was thrilled to do so. I was certainly familiar with his work. We met at the Algonquin Hotel, where he was staying. I had expected that we would be alone but it was not to be. One, possibly two film crews were at work. The full unpublished transcript runs 42 single-spaced pages, so this is just an edited selection from that transcript.

Two film-makers, Amalie Rothchild and Claudia Weil, come in, joining the small camera crew that has already begun to film us.

At a certain point, for privacy, I asked Ronnie to come into the bathroom (!) with me so that we might have a brief, private conversation. We did so.

PC: But I don’t think that telling the truth will immediately cause people to lay down their guns or take off their body armor, and we’ll all go out into the streets and celebrate life.

RDL: One may state the truth, but the stating of it doesn’t insure the triumph of it. More than that one cannot do, but state it in whatever is the most effective manner, according to time and circumstances that they dictate.

PC: If people put their bodies where their ideas are, they are frequently called “mad.” When someone speaks their truth, in a way, that is socially unacceptable—or in a way that is really terrifying and they’re going to be “crucified,” either by being socially labeled insane or being labeled criminal, or by having their spirits broken. I think that Wilhelm Reich was very good on this in the first three chapters of “The Murder of Christ.”

RDL: Some people got away with it more than others. I think that Erasmus got away with it. Here’s an eminently sane man “In Praise of Folly,” who, when people are freaked out all around him, he lampooned every establishment, power, money, the church, theology.

PC: How did he get away with it?

RDL: He kept on the move. He had powerful friends. He stayed with the right people. Like Voltaire; he just got away with it.

PC: Where would a woman have powerful friends like that who weren’t men?

RDL: It’s like being the court Jew in the Hitler regime. All the chiefs, including Himmler, the Nazis had one or two Jewish friends. They told them, “Oh nothing will happen to you.” Those one or two people they kept. If it’s just a matter of getting away with one’s skin, one’s name, which is something, isn’t it? I would certainly prefer to get away with my body. Women’s suffering has been stamped out as a historically recognized fact by the time male history starts to be written.

PC: Of course, if one can save one’s skin, that does not insure the triumph of one’s word.

RDL: Oh, no.

PC: What happened to your wonderful book “The Divided Self”?

RDL: In the first three or four years that it was published in this country it sold under 1,500 copies in all.

PC: I read through it in one night. I was a psychology major, an awful life, and that was a good evening.

Our 1972 conversation is now contained in a new book, R.D. Laing: 50 Years Since The Divided Self. The book was edited by two psychotherapists: Dr. Theodore Itten, past President of the Swiss Psychotherapeutic Association and Executive Editor of the International Journal of Psychotherapy, and Dr. Courtenay Young, formerly the resident psychotherapist at the Findhorn Foundation, an author, and an editor of the International Journal of Psychotherapy.