Recollecting Jewish History

by Michael Curtis

On Independence Day, July 4, 2020 protestors in Baltimore toppled a statue of Christopher Columbus and threw it into the harbor. On the same day, the Junipero Serra statue on Capitol Grounds was vandalized, toppled, and moved. Whether these events are to be seen as the erasing of history is arguable but as a minimum these were the latest examples of the reexamination of memorials in the U.S. that mean different things to different people. By contrast, on July 1, an announcement was made in Israel of an ambitious project to reconstruct the life of Jewish communities and the association of Jews with the culture of the Ottoman Empire. A vast digitized database of Turkish Jewish cemeteries has just been launched online and made available to the public.

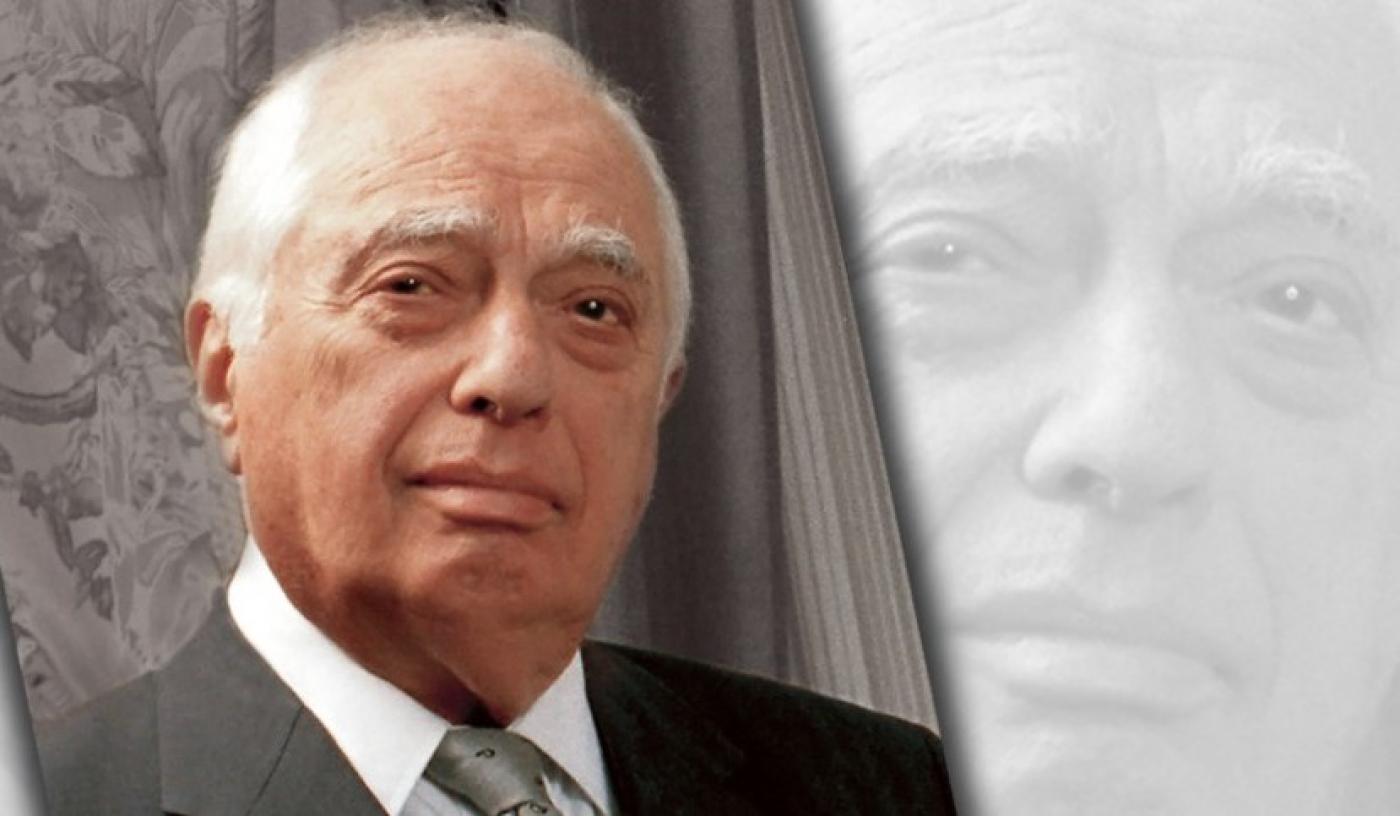

A key figure in the development of this project was Bernard Lewis, British-American scholar who died in 2018 aged 101, who can be considered the most erudite and influential historian and analyst of Islam and the Middle East in modern times. Lewis was a world authority not only on the history, religion, literature, and even poetry of the counties in the region, but also fluent master of a remarkable number of Middle East languages, Arabic, Turkish, Persia, and Hebrew, as well as of the usual romance languages, and even Danish and Russian.

In his long career, Lewis embraced an extraordinary variety of experiences, some of which were unusual for an academic, such as being a British intelligence officer in World War II, or being invited to meet with Pope John Paul II, Shah Mohammed Pahlavi of Iran, Anwar Sadat, and personnel at the White House and the Pentagon. He was also a Zionist advocate and robust defender of the State of Israel, as well as a voluminous author and commentator. He was not simply a closet intellectual but became in the latter part of his career a public intellectual, articulating his point of view in stimulating and challenging but undogmatic fashion.

Lewis influenced a mode of discussion. Though the term, “choc de civilisations,” had been used by Albert Camus in Tribune de Paris, July 1, 1946, it was Lewis’ important article, “The Roots of Muslim Rage,” in Atlantic Monthly, September 1990, that used the phase “clash of civilizations,” a clash between Islam and the West, that sparked international discussion and that influenced Samuel P. Huntington to write a book on the subject. Lewis warned the West. Islam had inspired a great civilization which by its achievements had enriched the whole world, but it also had periods when some of its followers were inspired by a period of hatred and violence, “It is our misfortune that part of the Muslim world today is now going through such a period, and much of that hatred is directed against us.” Lewis was the first scholar to understand that Osama bin Laden was the champion of an ideology of jihad and was a danger to the West.

His series of books and articles made Lewis a world renowned scholar, a Turkologist as well as Arabist, and most distinguished interpreter of Turkish history and Arab culture. He praised Islamic achievement in arts and science during the Golden Period, though also indicated the distortion of Islam that led to terrorism. Lewis was also the first to examine the Ottoman archives that were only recently opened, leading to a masterful book The Emergence of Modern Turkey, 1961. He stood his ground and differed from the accepted view that the massacre of 1.5 million Armenians by the Turks in 1915 was an example of “genocide.” His controversial argument was, “I do not say that the Armenians did not suffer terribly. But to make their tragedy a parallel with the Holocaust in Germany was rather absurd. Rather is could be seen as a struggle between two competing nationalist movements. “

Although a Jew, Lewis had no hesitation in writing about Middle East countries and their history. In partial explanation he wrote an article, “The pro-Islamic Jews,” about earlier Jewish writers, including Disraeli, who had written fairly and honestly on Islam and Islamic societies as he did himself. His subtle view of the Ottoman Empire was the fact that despite becoming a haven for Iberian Jews fleeing persecution, it was a mixed experience for Jews, who sometimes had times of prosperity, and at other times were persecuted, depending on the particular Sultan in power.

Lewis was honored publicly in many ways, not least by being the Jefferson lecturer for the National Endowment for the Humanities in 1990, the highest honor the U.S. government confers for distinguished intellectual achievement in the humanities, as well as being a Fellow of the British Academy and a Fellow of the Institute of Turkish Studies.

Not the least attribute of Lewis was his generosity to students, fellow academics, and to new ideas. The latest recognition of this generous trait appeared on July 1, 2020 Lewis with the announcement in Israel of the availability of a digitized computerized database in his honor. This database is the result of a project. “The World beyond: Jewish Cemeteries in Turkey 1583-1990.” The project is under the jurisdiction of the Goldstein-Goren Diaspora Research Center of Tel Aviv University, which obtained funds to upload the database and make it available to the public.

The idea of the database started in a conversation in the mid-1980s between Bernard Lewis and a Turkish friend, Nuri Arlasiz, collector of Ottoman art who wanted to save the Jewish cemeteries of Istanbul from being plundered or destroyed by natural causes. Jews lived in many towns in Asia Minor and each had its own cemetery. Arlasiz asked Lewis for help to save them. Around the same time, a number of Jews in Istanbul organized events commemorating the 500th anniversary of Spanish Jewish settlement in Istanbul, ancestors who had been expelled from Spain in 1492, and left for the Ottoman Empire. The events were headed by an industrialist named Jak Kamhi, born into a Jewish family in Istanbul, who was involved in public diplomacy and for a time advisor to the prime minister. Lewis agreed with the idea but had a different point of view, proposing that the Jewish cemeteries should be documented since they would have little chance of surviving without a live Jewish community.

Lewis consulted with Professor Minna Rozan, then head of the diaspora research center at Tel Aviv university, and later professor in the history department at Haifa University, who had written on the history of the Jewish community in Istanbul, and the transformation of the Greek speaking Jewish community of Byzantine Constantinople into an ethnically diverse Ottoman Jewish community. The Romaniote Greek speaking Jews, in the eastern Mediterranean, Balkans and Anatolia, were distinct from the Sephardic Jews.

As a result Minna Rozan went to Istanbul in 1987 to examine whether Lewis’s idea was feasible, and a plan was worked out by an agreement among a Turkish group, the Quincentennial Foundation, and the Annenberg Institute in Philadelphia, then directed by Lewis. Rozan, taking a sabbatical from her position at Tel Aviv University, spent two years 1988-1990 documenting the Jewish cemeteries in Turkey with a research team who sorted through over 100,000 photos of 61,022 tombstones to establish the database. Emphasis was put on the most ancient tombstones and those threatened by neglect or urban expansion. Some cemeteries have been destroyed, wholly or partially, by construction of the ring road around Istanbul.

When the resources available at Annenberg Institute ended, Lewis himself through Tel Aviv supported the project with a very generous gift which enabled the digitizing of the photos.

The research covers 28 different cemeteries, including a Karaite one in Istanbul and the Italian one in Istanbul, as well as those from communities in Western and Eastern Anatolia which ceased to exist after 20th century wars and immigration. The digitized database involves contents of the gravestones, the materials used, and ornamental elements. It claims to be the largest tombstone database in the world, coveting 400 years of Turkish-Jewish life. Any user can peruse the database to find a specific gravestone.

How gratifying that the Jewish heritage is not being erased.