Religion And Politics

by Michael Curtis

There’s a change in the fashion, there’ll be some changes made today, it’s time to seek something new. Secularism, indifference to or rejection of religion is increasing in the modern age, though religion continues to be important, partly because of the continuing confrontation between Radical Islam and the West, and the plurality of religious as well as political beliefs. A democratic state is supposed to be neutral with regard to religion, but this is not easy to sustain in practice. Every reasonable person will agree on the need for freedom of conscience and some form of separation of church and state, but religious commitment may clash with political demands.

The classic case illustrating the tension between religious adherence and civic duties is the action of Antigone in burying her brother for religious reasons, thus defying Creon’s decree. The modern version of this tension is present in the French law that makes it illegal for students in school to wear clothing or adornments that are explicitly associated with religion, and in Pakistani laws that ban “defamation of religion.”

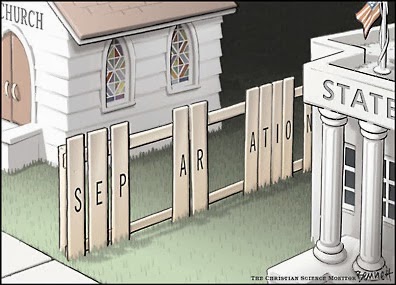

The issue of religion and politics has concerned the U.S. since its foundation. The country began with the First Amendment to the Constitution, “Congress shall make no laws respecting the establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” This Declaration was reinforced by Thomas Jefferson in his letter of January 1, 1802 to the Danbury Baptist Association where he used a metaphor in speaking of building a “wall of separation between church and state.” Metaphors have been influential in political analysis, witness Abraham Lincoln’s “house divided,” or Winston Churchill’s “iron curtain.” The problem is that Jefferson’s metaphor became accepted as a valid description of the relation of religion and politics in the U.S. and has been used to separate religion from public life ever since. But his words remained controversial with differences over the meaning of “wall,” which was distinct from the “non-establishment” of the First Amendment.

Paradoxically, Jefferson’s religious views were an important issue in the presidential election of 1801 which he won. Moreover, he was hardly a secular humanist, He endorsed federal funds to build churches, he signed bills that appropriated financial support for chaplains in Congress and the military, he attended church services in the House of Representatives, and on April 10, 1806, “earnestly recommended to all officers and soldiers, diligently to attend divine services.”

The interaction of religion and politics remains a crucial and controversial issue in the U.S. and elsewhere. Surprisingly, religion appears to be more important to U.S. citizens than to people in other countries since the polls report that religion plays a significant role in their lives. Public opinion polls indicate that 71% of the U.S. population identify themselves as religious, though the proportion is declining, partly because of more racial and ethnic diversity, partly because of immigration, and partly because of intermarriage.

An important factor in U.S. politics is that Christians, Protestants and Catholics, are overrepresented in Congress in proportion to their share in the population. About 88% of the present 116thCongress identify as Christian: 54% as belonging to one of the different Protestant sects, and 30% as Catholic. One significant difference is the variation between Congress and those unaffiliated with any religious group. About 23% of the U.S. citizenry say they are atheist, agnostic, or simply non-believers. In Congress only one person, Sen. Kyrsten Sinema (D-Ariz.), states she is religiously unaffiliated.

Over the last decade, governments, including those in China, Russia, and Indonesia, have imposed limits on religious activities, restrictions on religious freedom, religious beliefs and practice, and passed laws favoring particular religious groups, and these restrictions have substantially increased. This increase is also the case with hostile acts against people, such as those based on religious norms, harassment of women for violating dress codes, and harassment and violence by individuals and groups such as neo-Nazis. In addition, there are outbreaks of interreligious violence such as in the situation between Hindus and Moslems over Kashmir.

The religious-political issue erupts in various forms. One is the decision in 2009 by the European Court of Human Rights based in Strasbourg, in the case of Lautsi v. Italy, that banned the display of crucifixes in public classrooms, holding that the presence of a religious symbol in public classrooms has no justification, and violated the principle of secular education.

With its verdict in this case, the Court had entered the conflicting realms of politics and ideology. The Vatican opposed the ruling, arguing that the Court wanted to ignore the role of Christianity in forming Europe’s identity, and that it is wrong and myopic to exclude religion from education.

The problem is not simple.Catholic dignitaries, necessarily, have entered the world of politics, especially on sexual questions and above all that of abortion. They, especially the Vatican, are diplomatically active. Most recently, Pope Francis met with Alberto Fernandez, then a candidate and now the virtually elected president of Argentina since he beat his rival Mauricio Macri by 15 points in the primary election on August 11, 2019. Fernandez, first was a conservative, then became a member of the large Peronist party, Justicialist, adhering to principles of the dictator Juan Peron. Fernandez’s policies are difficult to pinpoint ideologically. But he formed a winning electoral alliance, the Frente de Todes. The importance of this is that it was at his meeting with the Pope that Francis urged Fernandez to unify the Peronist opposition, which had been previously defeated, and to reconcile with his then political enemy, the former president Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner.

Pope Francis in various speeches has indicated the main direction of his political leanings. In 2015, he spoke as the champion of the poor and dispossessed, and spoke of the need to find concrete solutions to combat widespread poverty and environmental destruction. He specifically attacked all powerful elites, drug trafficking, the nuclear arms race, and proposed an international juridical system.

Francis entertained Raul Castro at the Vatican, then visited Cuba. In 2015 he was critical of the U.S. for its sexual policies, and linked the “innocent victims of abortion to children who die of hunger or from bombings.”

On October 1, 2017 at the Italian town of Cesena he attacked corruption as the “termite of politics “ because it does not permit a society to grow. He called, in unusual and somewhat unclear language, for a kind of politics that is neither a servant nor an owner, but a friend and collaborator, neither fearless nor reckless but responsible and therefore courageous.

Though he has not mentioned them one wonders if Pope Francis is or was linked in some way to the group of left-wing bishops, the so-called St. Gallen group. The group stems from The Pact of the Catacombs, a semi-secret agreement signed by 42 bishops of the Catholic Church on November 16, 1965 in the catacombs of Domitilla near Rome before the end of the second Vatican Council. The agenda of the bishops was to end the richness, pomp, extravagant ceremony of the Church, and they agreed they would try to live like the poorest of their parishioners , to live according to the ordinary manner concerning housing, food, means of transport, and to renounce the appearance and substance of wealth, especially in clothing and ornaments made of precious metals.

Though the implicit message was the centrality of poverty, the message was largely forgotten except in Latin America where it became associated with liberation theology. Some bishops now regard Pope Francis as the symbol of the pact, especially since he leads a simple personal existence by living in a Vatican guesthouse, not in a mansion.

The question in American politics is the degree to which religious views affect secular loyalties and decisions, and whether freedom of religion is a natural right stemming from the Constitution. The founders of the U.S. Republic thought religion had an “instrinsic worth,” and was a social good. In Western culture the Bible, which sells a quarter of million copies every year, has influenced culture and politics. The intrinsic problem is the religious canons of Christianity and Judaism and the Pentateuch which provide spiritual nourishment do not provide automatic answers not only to questions of faith, as in the fierce dispute between Erasmus and Martin Luther in the 16thcentury, but more significant today to mundane questions. One recent issue: do American restaurants, which cannot discriminate on the basis of race or sexual orientation, have the right to refuse to serve individuals based on religious belief?

U.S. Catholic prelates are said to vote Democrat, and they, among other things, have denounced a border wall in the U.S. South, sought to abolish capital punishment, get universal health care coverage, reduce poverty. Yet Catholics can reach different conclusions on immigration, criminal justice reform, and above all on abortion or same sex marriage.

A 2016 Pew Research poll reports that 51% of Americans think abortion is immoral, and are critical 32% of homosexuality and, 8% of contraception use.

Change on this issue is difficult. 35 per cent of Congressional Democrats are Catholic. Dissenting Catholics have been punished or threatened.

In 2009, Cardinal Donald Wuerl, Archbishop of Washington was urged to deny Holy Communion to Rep. Nancy Pelosi for her support of liberal abortion laws.

Similarly, Senator Dick Durbin was in trouble 2018 when Bishop Thomas Paprocki of Springfield, Illinois refused to allow him Communion until he had repented of his “sin.” Durbin’s sin was that he was one of 14 Senators who voted against a bill that prohibited abortions starting at 20 weeks after fertilization. The Bishop knows that it is a sin to tell a lie. He should have known that Durbin was acting politically, not behaving immorally.