by Michael Curtis

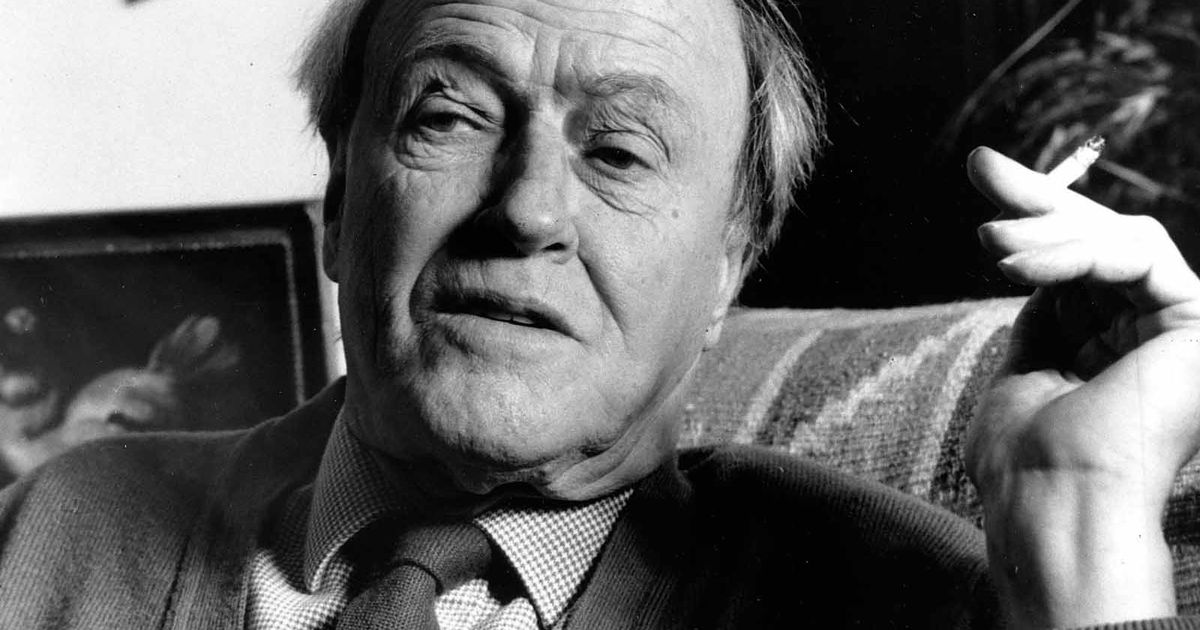

Roald Dahl

The family of Roald Dahl in December 2020 gave its version of what might be considered a Hanukkah present to the world, though it was not addressed to Jewish organizations. It issued a statement, deeply apologizing for the lasting and understandable hurt caused by some of Roald Dahl’s statements. Yet, it also said that his prejudicial remarks were incomprehensible to the family, and stood in “marked contrast to the man they knew and to the values at the heart of his stories, which have positively impacted young people for generations.”

Irrespective of that positive impact on young people, the prejudicial remarks of Dahl, an outrageous obsession with antisemitism, were not unknown. Indeed, he was open about this until the end of his life. In an interview with the New Statesman in 1983 he wrote “there is a trait in the Jewish character that does provoke animosity, maybe it’s a kind of lack of generosity towards non-Jews. I mean, there’s always a reason why anti-anything crops up anywhere. Even a stinker like Hitler just didn’t pick on them for no reason.”

Dahl reinforced this point of view in an article, written just months before he died in 1990 at age 76, in the Independent in 1990 in equally stark, if somewhat incomprehensible, fashion: “I’m certainly anti-Israeli, and I’ve become antisemitic in as much as that you get a Jewish person in another country like England strongly supporting Zionism. I think they should see both sides. It’s the same old thing: we all know about Jews and the rest of it. There aren’t any non-Jewish publishers anywhere, they control the media, jolly clever thing to do… that’s why the president of the United States has to sell all this stuff to Israel.”

Dahl’s other writings contained allusions to familiar antisemitic stereotypes: the financial power of Jews; their control of the media; newspapers are primarily Jewish owned; Jews were weak and submissive to Hitler but aggressive in Lebanon. As news of his antisemitism became known, the British Royal Mint in 2014 dropped plans to celebrate Dahl’s life with a coin commemorating him, saying he is not regarded as “an author of the highest reputation.”

Dahl was born in 1916 in Llandaff, Wales to Norwegian parents, went to boarding school at age of 9 and skipped university education. He served in World War II in the RAF as a pilot, was badly injured in a crash landing in Libya, and then spent some time during the war in the U.S. working on counter-intelligence, in effect a spy, and also on young wealthy women, one of whom was Clare Boothe Luce. He returned to Britain and became an author mostly of children’s books, nineteen in all, though he was also an author of adult novels, short stories and screen plays, including Chitty, Chitty Bang, Bang, and the James Bond film, You Only Live Twice.

Among the most well-known stories welcomed by children, are Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Matilda, James and the Giant Peach. Dahl said he conspired with young people to enter into a conspiracy with them against the grown-ups. Those grown-ups had mixed feelings, with some regarding Dahl’s work as tasteless, violent, and sadistic.

Many of his children’s books have been adapted for films, theater and TV, and have been phenomenally successful. At least 250 million copies of his books world-wide have sold though they contain macabre behavior, twisted tales, ghosts, villains, and bigoted and racist remarks, and a mixture of gruesome and comic. His estate in recent years made lucrative deals with Hollywood. Netflix is reported to have paid $1 billion in 2018 for the rights to 16 of his works.

The Dahl case is another example of a dilemma that will never be satisfactorily resolved and for which no categorical answer is possible. Can one or should one admire and honor highly gifted individuals for their creativity or works of art or fiction though they have serious flaws in their character and behavior? Can the pleasure derived from reading or seeing the work be reconciled with distaste or loathing of the author? It has long been problematic to separate the art from the artist in any evaluation of an individual one. One can appreciate Picasso’s “Les demoiselles d’Avignon” and his “Guernica” while conscious of his cruel treatment and abuse of women: for him “women are machines for suffering.” Paul Gauguin may be accepted as a giant of post-Impressionism, but he exploited the pubescent girls he painted. Listeners may consider Tristan und Isolde a masterpiece but Richard Wagner, is notorious for his antisemitism, particularly in his essay “Das Judenthum in der Musik,” (Jewishness in Music), and his opinion of “the harmful influence of Jewry on the morality of the nation.” Not surprisingly, though the decision is controversial, the Israel Philharmonic will still not play the music of Wagner.

The most banal adage is that no one is perfect; that’s why pencils have erasers. Unpleasant references may be found in Shakespeare but they do not affect the majesty of his poetry, nor opinions of what is known of his life. But the issue is different for those holding untenable opinions, or where, to use Newton’s third law, there are equal and opposite reactions to an action. Reflection on the dilemma can start with the famous, and influential, dictum of T.S. Eliot. “I have assumed as axiomatic that a creation, a work of art, is autonomous.” That creation should be evaluated on its own merits without regard for the persona of the author or creator.

An early controversial example of the issue, should aesthetic, art, literary products be considered apart for the creator, was the case of Ezra Pound. He was given the Bollingen prize in 1948 for his “Pisan Cantos,” though he had delivered pro-Fascist talks in Italy during World War II, and had been a long time ardent follower of Mussolini. But the case of the French writer Louis-Ferdinand Celine is different. He developed a much admired new style of French writing in his novels, using slang, and colloquial language, but he was a Nazi sympathizer, a repellant anti-Semite who influenced a generation of collaborators in Vichy France. Unlike the case of Pound who was honored, French authorities in 2011 refused to include Celine in a list of French cultural personalities to be commemorated.

A related polarizing topic of recent debate is the concept and implementation of “cancel culture,” a modern form of ostracism from professional public activity. This entails withdrawing support from or opposing platform appearances by public figures considered to be responsible for offensive or objectional behavior to people, cultures, or ideologies. They may be subject to boycotts or disciplinary action. A recent surprising example is strong criticism of the popular Harry Potter novelist J.K. Rowling for her beliefs about transgender rights and biological sex. The danger in this cancel culture attitude is imposition of controls of free speech and expression.

An unrelated example of another change in moral climate, partly due to the Me Too movement against sexual abuse, is the increase of allegations and prosecution of prominent celebrities who have been held accountable for sexual harassment, assault, and other misconduct. Among those who have been punished or lost their jobs on being held guilty are performers like Johnny Depp, Bill Crosby, Kevin Spacey, and perhaps Woody Allen.

No one should call for the banning of the books of Roald Dahl, even if one holds them tasteless and sadistic, and dislikes his dark fantasies of the world as a horribly unpleasant place. But neither should they favor prizes or awards for him, nor excuse his antisemitic statements. Moreover, Dahl did not carry a cloak of impenetrable virtue. He was unkind to and probably jealous of Salman Rushdie, when the fatwa against him was issued, calling him a dangerous opportunist for his Satanic Verses. He was a serial womanizer, cheating on his wife with many women, including Gloria Vanderbilt. Dahl was mean and irritable, and his wife, the actress Patricia Neal called him “Roald the Rotten.” And why did he visit Adolf Hitler’s Berchtesgaden retreat in 1951?

One Response

RD’s semitism, whether pro or anti, is only one measure of his intelligence. Similarly for the rest of us. The respect he’s received for his somewhat controversial writings seems well-deserved. The question arising from center field (I dare not say ‘left’ or ‘right’ field) is: What factors comprise the quality of civilization? Are they mainly excellence of the arts, sciences, philosophies, literatures, …or somethings else? Does expressions by the society of kindness, fairness, minimal contradictions in social expressions/behavior, codes of communication (taboos, limits on use/intensity of insults, …). How to judge RD and ourselves? Who voted for the Setters and Keepers of the Civilization Standards? Ought we not to have a multi factor index quantifying and quality-fying the nature and degree of our personal civilization? //. To keep it simple, in baseball terminology, are we capable of discerning the difference twixt our arses and third base? Oops! Time again for my Martian overseers to check the tightness of my strait-jacket.