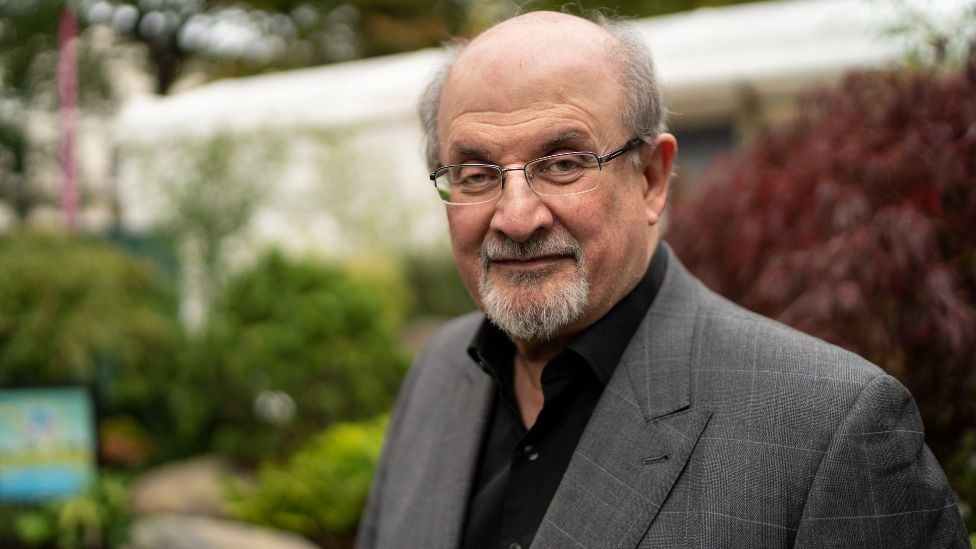

Salman Rushdie, a prophet of God

by Lev Tsitrin

Sometime in 1868, annoyed by the wild success of The Gates Ajar — a novel describing heavenly afterlife based on conventional Christian beliefs, Mark Twain embarked on describing what was to him a “sensible” heaven. The subject fascinated him, but he deemed his story unfit for publication as too offensive for the general public, only agreeing to have it published some forty years later, towards the end of his life. Published as “Extract from Captain Stormfield’s Visit to Heaven,” it was met with warm bemusement rather than outrage.

The salient feature of Mark Twain’s heaven is that it is founded on absolute justice. His heaven is very much stratified, with distinctions of class and rank strictly codified in hierarchy, and followed in everyday life, serving — paradoxically — the interests of both the high- and the low-ranking inhabitants. It is a picture of a true meritocracy: unlike the earth where one’s success is not necessarily proportionate to talent (or is not even due to it, the success largely being determined by one’s social and political connections, not merit), in heaven, the principle of just reward reigns supreme: one’s place in the heavenly hierarchy is determined not by the past, earthly success, but by one’s inherent talent and merit, even if they have never come to fruition on earth, or been acknowledged or rewarded.

Of this heavenly social structure, one gets only a glimpse. There are archangels, prophets and patriarchs who are themselves subdivided by rank. No one in the higher ranks is accessible to the common folks, or has time for an appointment. Prophets outrank patriarchs, “The newest prophet, even, is of a sight more consequence than the oldest patriarch.” The same source — “an old bald-headed angel by the name of Sandy McWilliams” who was in his former life a New Jersey cranberry farmer (and who continues cranberry farming in heaven, it being his natural bent), explains that in heaven, poets are considered prophets, and as a result of the pecking order, “Adam himself has to walk behind Shakespeare.” A revealing dialogue follows:

“Was Shakespeare a prophet?”

“Of course he was; and so was Homer, and heaps more. But Shakespeare and the rest have to walk behind a common tailor from Tennessee, by the name of Billings; and behind a horse-doctor named Sakka, from Afghanistan. Jeremiah, and Billings and Buddha walk together, side by side, right behind a crowd from planets not in our astronomy; next come a dozen or two from Jupiter and other worlds; next come Daniel, and Sakka and Confucius; next a lot from systems outside of ours; next come Ezekiel, and Mahomet, Zoroaster, and a knife-grinder from ancient Egypt; then there is a long string, and after them, away down toward the bottom, come Shakespeare and Homer, and a shoemaker named Marais, from the back settlements of France.”

“Have they really rung in Mahomet and all those other heathens?”

“Yes—they all had their message, and they all get their reward. The man who don’t get his reward on earth, needn’t bother—he will get it here, sure.”

“But why did they throw off on Shakespeare, that way, and put him away down there below those shoe-makers and horse-doctors and knife-grinders—a lot of people nobody ever heard of?”

“That is the heavenly justice of it—they warn’t rewarded according to their deserts, on earth, but here they get their rightful rank. That tailor Billings, from Tennessee, wrote poetry that Homer and Shakespeare couldn’t begin to come up to; but nobody would print it, nobody read it but his neighbors, an ignorant lot, and they laughed at it.”

The story keeps rolling in the same vein before the subject changes — but we are in the right place in it to evaluate Salman Rushdie’s place in Mark Twain’s heaven’s hierarchy of prophets. When Rushdie’s time comes to be received at the pearly gates — an eventuality which one “Hadi Matar, a 24-year-old New Jersey man” tried to bring around by viciously stabbing him (though, as the New York Times further informs us, “The New York State Police said at a news conference on Friday afternoon that there was no indication of a motive”), where would Rushdie march in this distinguished heavenly parade of prophets? Would he be placed behind Mahomet, or ways ahead of him?

This is a tricky question as it puts me in the shoes of a literary critic — which I am not; and yet, the answer is easy. I did read an essay by Rushdie long ago — and I read the Koran (admittedly, in translation) — and there is no comparison; at the most charitable, the Koran is tenth-rate literature at best. In fact, I wonder whether Mark Twain ever read it; it seems likely that he assigned Mahomet such high position in his heaven just from hearsay — or perhaps from the overdeveloped sense of guilt and obligation that resulted in today’s “political correctness,” “affirmative action,” or “multiculturalism” — none of which can have any place in Mark Twain’s ultimately just heaven, where people are judged by their true merit alone — and by nothing else. That Mahomet should rank above Shakespeare is a joke — but Mark Twain was a humorist, after all.

Needless to say, Moslems are very jealous about Mohamed’s claim of prophethood. They see him as a “seal of prophets” — the final prophet ever sent to humans — and are immensely annoyed and offended when anyone else steps forward claiming prophethood (this is the reason for the enmity towards Baha’i faith that was established in 19th century — it is fine and good to be a prophet before Mohamed, but not after him). Yet why this should be the case, is not at all clear — and in fact, doesn’t make any sense: self-declared prophets (there is no other kind, of course, Mohamed being one such) popped up every now and then with a good deal of regularity before Mohamed, and there is no reason whatsoever why they should not be appearing after him. This clearly made no sense to Mark Twain — though he likely never knew about Mohamed’s presumed uniqueness and finality. Clearly, by Mark Twain’s criteria, Rushdie is a prophet (as was Mark Twain himself for that matter, though he was perhaps too modest to say it). It would be presumptuous for me to rank Rushdie near Billings — or even near Shakespeare, for that matter — but clearly, Rushdie belongs in that crowd of prophets. Whether Mohamed belongs there, is much more doubtful.

This settled, one final thought: amidst all the nonsense that is now going on (including the stabbing of Rushdie, though this particular instance of human idiocy is far from the only one we witness on a daily basis), we need clear, sane voices like Rushdie’s — be they prophetic or not — right here on earth. Whatever reception may ultimately await Rushdie in heaven, I hope he makes it for now, coming out of surgery healthy and strong — and keeps giving us his visions despite all the jealous venom and hate from the followers of a much lesser writer from fourteen centuries ago by the name of Mohamed.

Lev Tsitrin is the author of “The Pitfall of Truth: Holy War, its Rationale and Folly”