Shabbat Toldot Shalom

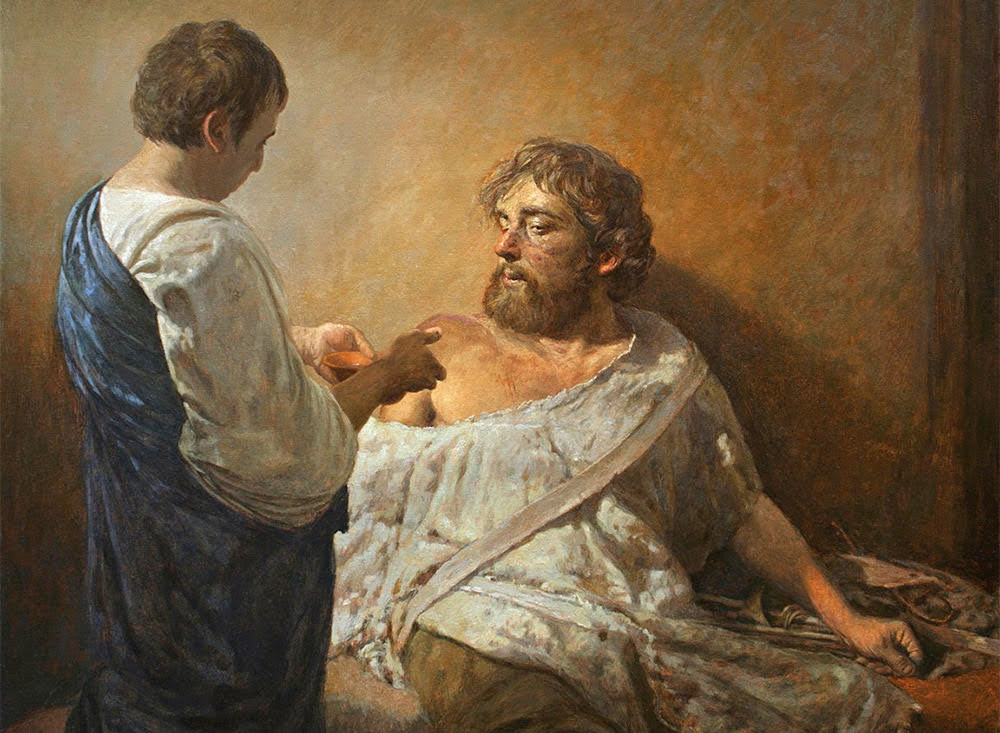

Photo: “Esau and Jacob” by Andrei Mironov, 2014.

by Phyllis Chesler

Twenty three years ago, I contemplated the relationship between older and younger brothers in Bereshit in this way:

The older brothers are usually “men of the field,” hunters with hearty appetites, men of war. I have always felt grave, maternal compassion for Cain (who “worked the earth”), and for his brother-descendants: Yishmael, that “wild ass of a man,” (Genesis 16:12), who became an “expert archer,” (21:20), and Esav, the hungry hunter.

Cain, the world’s first older brother, worked in the fields: he is our first “ish ha sadeh.” Abel, “Hevel,” (haval—a passing, expired, breath, mere vanity?) whose offering God accepted, was a shepherd. (Genesis 4:2). In other words, Hevel has been blessed and Cain, therefore, feels cursed. Immediately, God becomes a psycho-analyst. Why feel so dejected, God asks Cain, why not try again? (“Lama chara lach v’lama naflu panecha? Halo im-taiteev si’ait?” “Why are you angry and why do you look so crestfallen? If you try again and do well, there is forgiveness, but if you do not improve, sin rests at the entrance.” (Genesis 4:6-7).

Here, we have it, and it might easily also be the root of antisemitism: The brother whose offering God accepts, is perceived as blessed by God. This, in turn, enrages and shames his brother. Cain’s envy, born of heartbreak, is so great, Cain’s capacity to struggle with it, so slight, that he kills Abel. “If I’m not the Chosen one, the bearer of the Blessing, then let there be no blessing-bearer.” Cain’s cry to God: “My punishment is greater than I can bear,” “Gadol avoni meenso,” (Genesis 7:13), is echoed by Esav when he cries out to Yitzhak: “Have you not saved a blessing for me”? “Halo atzalta lee b’racha?” (Genesis 27:36).

The Biblical Esav is an entirely sympathetic figure. Loved by his father but not by his mother, who preferred her “tent-dwelling” younger son. I am puzzled by his eventual rabbinic demonization as Amalek and Edom—all the more so because Esav is also rabbinically praised for honoring his parents e.g. he hunts for his father, and remarries to please his mother. There is something simple and good-hearted about this ruddy, reddish, hairy, hunter-brother who narcissistically relishes his red, look-alike lentil-porridge, who is at home in the rough-and-tumble of this world, who is satisfied when his senses are satisfied.

Slowly, I am learning that sharing the same womb and the same father is no guarantee that one will share one’s brothers’ character or destiny.

Today, I see other themes and have different questions. Since Rivka is so clearly chosen by God for Yitzhak and is so obviously Sarah’s spiritual heir; why, then, is she also an “akara,” barren? Why does she need Yitzhak to pray for her when she has her own direct relationship with God, one that is even more powerful than Yitzhak’s? Why is her pregnancy so painful? Was this God’s only way of teaching her that her twins must go their separate ways, that she must keep this secret from her husband, and that she must herself send her preferred son far away in order that he truly inherit the birthright, the blessing, the covenant?

And then, there’s this discordant note. Immediately after Esav sells his birthright, there is another famine in the land. The nearly blind Yitzhak settles in Gerar. How is it possible that the son follows so closely in Avraham’s footsteps? Yitzhak also tried to pass the beautiful Rivka off as his sister, lest “the local men (in Gerar) kill me in order to have her?”

Are beautiful women all cursed in this mans’ world?