Smoldering Passions In Lush Algiers

by Hugh Fitzgerald

Sally Magnusson, author of the just-published The Sealwoman’s Gift, has given us a story which takes an historical event — a Muslim raid on an Icelandic village in 1627 during which 400 Icelanders were seized and brought back as slaves to Algiers — and from this core of truth weaves a fantastic tale that lovers of romance novels may enjoy, but lovers of the truth, on the other hand, will find appalling..

The main protagonist is Asta, an Icelandic woman who with her husband Olafur, a parson, and their three children (the third is born on the privateers’ ship, in conditions of utter filth) is taken to Algiers, where they are all enslaved, she to become part of the harem of Cilleby, a rich Arab, while her two daughters disappear into other harems, and her young son similarly is separated from her, having been bought, raped, and converted to Islam by his new master. He will ultimately become a Muslim raider himself. Her husband, too, becomes a slave in one of the bagnios (slave-houses), and after years of captivity he is sent by the bey of Algiers to obtain a ransom for himself and his wife from the King of Denmark (Iceland then being a Danish possession), which he does indeed obtain, and Olafur and Asta return to Iceland, their three children left behind, to their various fates, in Algiers.

A great deal of the book is devoted to descriptions of their surroundings. Iceland is cold and miserable, while in Algiers everything is sunny and lush, in sharp contrast to frigid Iceland, and Asta gradually succumbs to this sensual luxuriance in the harem. A reviewer gushes: “We can smell the spiced perfumes of the roof garden harem in Algiers; the turf and mud of Iceland’s bleak coastline; feel the caress of silks, and the slice of frozen sea winds cutting across chapped cheeks.” Naturally Asta prefers the “spiced perfumes of the roof garden harem” to the “turf and mud of Iceland’s bleak coastline,” and “the caress of silks” to the “frozen sea winds cutting across chapped cheeks.”

She fashions stories from Icelandic sagas and folk tales, especially those about a fabled “Sealwoman” (hence the novel’s title), telling them to other women in the harem (one is prompted to ask: in what language?) and to her master Cilleby, for whom she is developing a passion, and he, it seems, is becoming ever fonder of her.

The real treatment of Christian slaves in Algiers is scandalously scanted in this fable. We are never told that slaves were so badly treated that, despite the threat of endless beatings if they tried to escape, they continued to take the risk. They made repeated efforts to flee their cruel masters, and seldom succeeded. Among those who tried to escape was the most famous of all Christian “Algerine” slaves, Miguel de Cervantes, who spent five years (1575-1580) as the slave of a convert to Islam, Hassan Veneziano, who during three of those years (1577-1580) was the regent of Algiers. Cervantes made four attempts to escape, and never forgot the brutal treatment he endured, allusions to which can be found in such episodes as “The Captive’s Tale,” in Don Quixote. Had he not finally been ransomed and returned to Spain, but instead made to spend the rest of his life as a slave in Algiers, the course of Western literature might have been different.

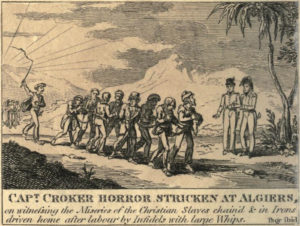

The horrors of slave-life in Algiers were well-known to Europeans (but are not, apparently, to Sally Magnusson), and were depicted in popular prints, such as this British print from 1815:

“Captain Croker horror stricken at Algiers, on witnessing the Miseries of the Christian Slaves chain’d & in Irons driven home after labour by Infidels with large Whips.” (The “Infidels with large whips” were in the service of their Muslim masters, and tasked with keeping other Infidels in check.) Additional information about the source: “The cruelties of the Algerine pirates, shewing the present dreadful state of the English slaves, and other Europeans, at Algiers and Tunis; with the horrid barbarities inflicted on christian mariners shipwrecked on the north western coast of africa and carried into perpetual slavery. authenticated by Mr. Jackson, of Morocco; Mr. MacGill, merchant and by Capt. Walter Croker, of His Majesty’s Sloop Wizard. Who in last July (1815) saw some of the frightful horrors of Algerian Slavery.”

Nor do we learn from her novel about the conditions of the Christian galley-slaves:

Slaves in Barbary fell into two broad categories. The ‘public slaves’ belonged to the ruling pasha [bey], who by right of rulership could claim an eighth of all Christians captured by the corsairs, and buy all the others he wanted at reduced prices. These slaves were housed in large prisons known as baños (baths), often in wretchedly overcrowded conditions. They were mostly used to row the corsair galleys in the pursuit of loot (and more slaves). This work was so strenuous that thousands died or went mad while chained to the oar.

During the winter, the corsairs stayed mostly in port, and these galley-slaves (galeotti) worked on state projects. They quarried stone, built walls and harbor facilities, even constructed new galleys. Each day they would be given perhaps two or three loaves of black bread – ‘that the dogs themselves wouldn’t eat’ – and limited water; they received one change of clothing every year. Those who collapsed on the job from exhaustion or malnutrition were typically beaten until they got up and went back to work. The bey of Algiers also bought most female captives, some of whom were taken into his harem, where they lived out their days in captivity. The majority, however, were purchased for their ransom value; while awaiting their release, they worked in the palace as harem attendants.

Many other slaves belonged not to the pasha but to private parties. ‘Their treatment and work varied. Some were well cared for. Others were worked as hard as any ‘public’ slave, in agricultural labor, or construction work, or selling water or other goods around town on his (or her) owner’s behalf. They were expected to pay a proportion of their earnings to their owner – those who failed to raise the required amount were ordinarily beaten to encourage them to work harder.

Slaves were resold, often repeatedly. As they aged their value naturally decreased, and owners were glad to get rid of them. The most unlucky ended up forgotten out in the desert, or in the Turkish sultan’s galleys, where some slaves rowed for decades without ever setting foot on shore.

In the romance novel of Sally Magnusson, there are occasional oblique references to the difficult life of the slaves, but without the details — the malnutrition, the constant beatings, the hard labor, the one change of clothes a year. Magnusson plays down the Christian slaves’ unspeakable condition in Algiers — they were despised not just because of their status as slaves, but also because they were Infidels, described in the Qur’an as “the most vile of creatures.”

While an occasional master would prove to be kind, many more were cruel, and for Europeans, the stories that they heard from those who had escaped or been ransomed filled them with horror and dread. All of this Magnusson deliberately overlooks. For that kind of permanent misery would get in the way of her love story, of growing passion between Asta and Cilleby. She might have written a serious historical novel, with a truthful depiction of Islam’s slave masters, and of the 1.5 million European Christians they enslaved. She chose instead to produce an up-market variant on all those romance novels that play on the sexual attraction of The (Deep-Pocketed) Other, and have an Arab prince as the dreamily alluring subject for a young lady’s passion. Think of Rudolf Valentino as The Sheik. Think of Lady Diana, and her liaisons with a Pakistani doctor, Hasnat Khan, who had, she gushed, “dark-brown velvet eyes that you could just sink into,” and with an Arab playboy, Dodi al Fayed — now there are examples of “othering” for you. In making up this story of growing passion between Muslim master and Christian slave, did Magnusson ever recognize the banality of her theme — the love that develops between white girl and dark lover, sex-slave and master? Heaving passions, smoldering looks, what’s not to like?

And please, let’s not have any unpleasant mention of what Muslim grooming gangs did in Rotherham, or what ISIS did to Yazidi and Christian girls in Syria and Iraq, or what happened to those kidnapped schoolgirls in Chibok. All that merely gets in the way of a touching love story, set against the background of “spiced perfumes in the roof garden harem,” and the “caress of silks,” and the froufrou of dresses worn by the Pasha’s favorite female slaves.

If you would like to learn about the conditions that 1.25 million European men, women, and children, seized by Muslim corsairs and brought back to North Africa, endured as slaves, this book is not for you.

If, on the other hand, you are a devotee of romance novels in the Barbara Cartland vein, especially those situated in exotic and sensual climes, and you’ve run out of things to read in the Second Chance For Love series, then The Sealwoman’s Gift may be just the ticket.

First published in Jihad Watch.