My funny Valadon, sweet comic Valadon, your looks are laughable, you make me smile with my heart, yet, you’re the favorite work of art of the Barnes Foundation.

Fifty years ago the question was raised why are there no great women artists. In a now famous article Linda Nochlin, then a young professor at Vassar College, questioned why there were no women artists comparable to Michelangelo or Leonardo da Vinci. Nochlin and other feminist art historians laid out the reasons; our society thinks of men rather than women as great minds–creators and inventors. Therefore, women were denied opportunities. For instance, they were not allowed to attend art schools where they were would have learned how to draw the human figure. Nevertheless, in each period of Western history, there have been women artists who have been influential, but until the rise of feminist art history in the early 1970s, they were left out of art history, not seen in museums, nor was their work sought in the art market.They were not considered important simply because they were women.

Thanks to 50 years of art historical research by feminist art historians restoring the history of women artists there is little need now to point out the contributions of Artemisia Gentileschi or Angelica Kaufmann in the past, let alone the many contemporary or recent past women artists, Frida Kahlo, Georgia O’Keeffe, Paula Rego, Helen Frankenthaler, Faith Ringgold and Miriam Schapiro for example.

Women were long taken less seriously as professional artists than men. They were largely barred from artistic professions, art schools, and educational training until the 1870s; lack of patronage along with social, cultural, political factors limited opportunities for women; lack of gallery representation and dealers; different definitions of art and of what constituted quality; disparagement and undervaluing of certain art mediums, such as textiles and clay, more likely to appear in work of women; changing taste of collectors; balancing a career which could conflict with marriage and motherhood. Women had to compete in a world dominated by men, and in a society that ignored individuals and groups due to factors of gender, ethnicity, and class.

For fifty years, and largely because of the feminist movement, there has been an attempt to correct misperceptions, to illuminate women’s appropriate place in the history of art. Feminist theories have shed light on the reality that the contribution and role of women in art has not been as recognized as women deserved. Until the rise of feminism, as a social justice movement, women artists were not accorded their rightful place in history. But in spite of current changes in perceptions of women, their abilities, skills and contributions are still undervalued and often invisible, and women artists still lack opportunities in exhibitions or gallery representation to exhibit their work .

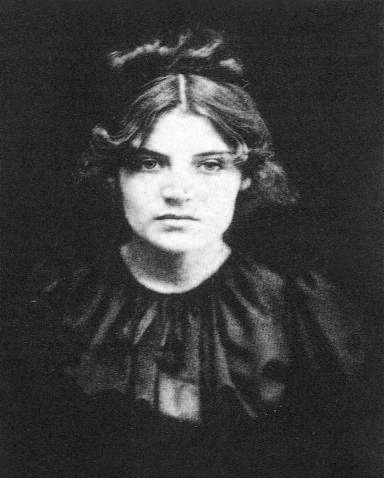

An example of the problem is the life of Suzanne Valadon, born in 1865, who died aged 72, in 1938, whose fame and artistic recognition, after some success, had dimmed in her later years. Ironically, she was overshadowed not only by male art peers and by a few women such as Mary Cassatt and Berthe Morisot, but also by her own son, Maurice Utrillo. Moreover, she cannot be fully associated with any particular art movement, though she touched on both post-impressionism and expressionism. She is one of many artists of merit who are unjustly neglected and unexplored for various reasons, including bias in gender, ethnicity, and class.

Although there are no works by Suzanne Valadon in collection of The Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia, the museum is currently holding an exhibition, “Susan Valadon, Model, Painter, Rebel” containing 54 works, the first major U.S. exhibition of her works, thus allowing appraisal of her artistic importance.

Valadon was a conspicuous figure in late 19th and early 20th century Paris, then the center of extraordinary, almost unparalleled, artistic creativity, concentrated in the area of Montmartre. With her open bohemian and maverick life style, the streets of Montmartre were home to Valadon with their excitement, celebration of love, and ideas.

Marie -Clementine Valadon was born in the village of Bessines-sur-Gartempe, Central France, in 1865 to an uneducated and unmarried mother who was a washerwoman. The family moved to Paris when she was five. She worked at odd jobs as a youngster, and at age 15 joined a private circus where she injured her back. She then became a model, posing for ten years and being a friend and often the lover of a number of cultural personalities. Among her intimates were, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Henri Toulouse-Lautrec, the composer Erik Satie, and Gustave Wertheimer. Toulouse Lautrec named her “Suzannne,” as in Susannah, the beauty spied on by lecherous elders, and painted her in a Portrait, 1885 and in the Hangover,1887, Renoir painted her in three well known works, Dance in the City, 1883, Dance at Bougival, 1883, and Three Bathers 1884.

Valadon was a habitue of Le Chat Noir, a Paris night club, the first modern cabaret, where she meet Miguel Utrillo. He claimed to have fathered her child Maurice Utrillo when she was 18, though his paternity has been challenged.

Valadon made the transition from being artist’s model, and often mistress, to becoming a maverick artist, first by drawing, mostly in pastel and charcoal, and then painting. She was too poor to have had art lessons, but she learned from the artists for whom she modeled. They were great masters and she took the best of their teaching. Degas recognized her talent for drawing and taught her lessons in printing. He recommended her for exhibition in the Salon de la Société Nationale des Beaux Arts. In 1894 five drawings were accepted. She was admitted, the first woman artist to have her work shown at the Salon des Beaux Arts.

She explained, “I found myself, I made myself, and I said what I had to say.” She did this in an output of 300 drawings, 50 oil paintings, 30 etchings, and prints and dry points She had what she had to say in her portraits , nudes, and still lives, with themes of herself, female desire, women’s experiences in society, women at various stages of toilet, using vibrant bold colors, bold strokes, intense black line, loose brushwork. Her nudes, still painted into her 60s, are remarkable with their curvy bodies and details usually not depicted such as their public hair. She was fond of self-portraits, including family portraits such as the one in 1912 where she is the strong figure in a quartette of mother, lover and son in a sad mood. At age 67 she painted a self-portrait, wearing only a necklace, and her face, a visage of mixed emotions.

Valadon’s work is unusual for a woman artist of that period. Males are presented in a sexualized way. This is evident in a strong large work, 1914, with three life sized muscular nude men casting fishing nets, one of which covers the penis of one of them, and all are painted as objects of lustful desire. She painted her friends, family, and above all nudes, with no idealization or subjecting them to the male gaze.

Valadon was an independent figure, as the Barnes Exhibition displays. A few examples may illustrate the point. Her painting, The Blue Room 1923, is reminiscent of Odalisques by Titian and Ingres, which are images of erotic mythological pastoral, but different in meaning, painted in thick lines and bold colors..She portrays the figure on a sofa as a confident mature woman at ease, wearing loose green stripped pants, and a pink camisole, smoking a cigarette, books at her feet, a commanding presence. Her image of Adam and Eve, 1909, is of an older woman and a much younger man , painted when she was 44 and her lover at the time Andre Utter was 23. Susanne was the femme fatale, an older woman prepared to seduce her partner, two fleshy bodies, with both reaching for the apple. Fig leaves were added later to the painting to cover the male genitalia. Noticeably, there is no serpent in the picture, only the forbidden fruit.

The Joy of Life 1911 reveals that she shared the same interest in classical themes shown by Renoir, Cezanne, and Puvis de Chavannes in their paintings of Eden with nude figures. Contrary to Renoir and Cezanne, Valadon includes figures of both genders (Renoir’s paintings with this theme only include women).

Thoughout her work Valadon presents women as equals with the same passion, and sexuality as men.In her self-portraits and nudes, she’s not afraid of showing wrinkled and sagging skin, representing the body as it changed with no attempt at prettiness.

The fundamental irony is the fact that her son Utrillo, who became part of the art canon, is represented in the permanent Barnes collection by 12 paintings but she is not included at all. Not only did she have her career as an artist, she also had to be a mother long after Maurice was grown. He suffered from mental health problems, and was turbulent, violent, often arrested. Yet she took care of him throughout his life. He died before she did, at age 37.

The funeral of Valadon was attended by many celebrities, including Pablo Picasso, George Braque and Andre Derain. A fitting memory is of her as a role model, an equal of male contemporaries, putting her in her rightful place in feminist art history.

- Like

- Digg

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link