The Ahmadi Abdus Salam and Muslim Nobel Prizes

by Hugh Fitzgerald

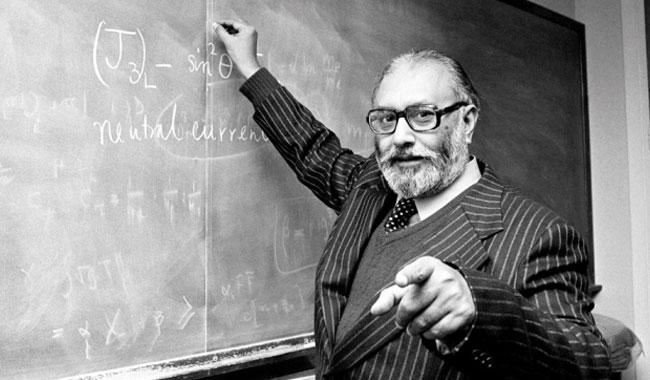

In “The Nobel winner who couldn’t call himself Muslim,” by Pooja Singh in LiveMint Thursday, we read about Anand Kamalakar’s “Salam: The First ****** Nobel Laureate,” which “follows the life of a Pakistani physicist who achieved great feats but was ostracized by his own countrymen.”

Abdus Salam shared the Physics prize with Stephen Weinberg and Sheldon Glashow. He was an Ahmadi, which meant that in his own country of origin, Pakistan, he was not considered to be a real Muslim, and on all official documents in Pakistan he was not permitted to identify himself as a Muslim, but only as an Ahmadi. Even on his gravestone, which originally bore the word “Muslim,” that word has been effaced to make sure everyone knows he was not a Muslim. If Muslims do not consider him to have been a real Muslim, either in life or in death, why should he be considered as such? The Pakistani government proclaims this Pakistani a non-Muslim. Who are we Infidels to differ?

Salam went to England just after getting his MA in Pakistan. At Cambridge, he got a double-BA, and then a doctorate from the Cavendish Laboratory, finally completing a BA degree with Double First-Class Honors in Mathematics and Physics in 1949. Then he received his doctorate, again from Cambridge. He returned to Pakistan, but at the time of he murderous anti-Ahmadi riots in Lahore, he promptly left Pakistan and returned to Cambridge, as a professor of mathematics, and then in 1957 took a chair at Imperial College, London, and went on with colleagues to set up the Theoretical Physics Department at Imperial College.

In 1957, Punjab University conferred an honorary doctorate on Salam for his contribution in particle physics. The same year, Salam launched a scholarship program for his students in Pakistan. Salam retained strong links with Pakistan, and visited his country from time to time. At Cambridge and Imperial College, he formed a group of theoretical physicists, the majority of whom were his Pakistani students. In 1959, at age 33, Salam became one of the youngest persons to be elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS). Salam took a fellowship at Princeton University that same year. He returned to Pakistan in 1960 to take charge of a government post, but within a few years had decided to return to Europe. In 1964, Salam founded the International Centre for Theoretical Physics (ICTP) in Trieste, in the northeast of Italy, and served as its director until 1999.

He returned to Pakistan later, but in 1974, Abdus Salam left Pakistan again for London in protest, after the Parliament of Pakistan passed unanimously a bill declaring members of the Ahmadiyya movement to which Salam belonged to be non-Muslims. The epitaph on his tomb initially read “First Muslim Nobel Laureate.” The Pakistani government removed “Muslim” and left only his name on the headstone. Being an Ahmadi, according to the definition provided in the Second Amendment to the Constitution of Pakistan, meant that one could not be considered a Muslim.

Muslims take a great interest in who is awarded the Nobel Prize. They know that unflattering comparisons are always being made with Jews — they do it themselves — who, with less than .0.2% of the world’s population, have received about 22.5% of the Nobels. This means the percentage of Jewish Nobel laureates is at least 112.5 times or 11,250%, above average. Muslims, on the other hand, who make up about 24% of the world’s population, have received — at most — 12, or 1.4%, of the Nobels. Should Abdus Salam be counted as a Muslim Nobel winner, or as a non-Muslim Ahmadi Nobel winner, as his own country insists? It makes more sense, given the ferocity of the campaign to deny Ahmadis the right to be considered Muslims, not to question but to accept that Abdus Salam was not, for most Muslims, a Muslim. All of Salam’s education in science, beyond his first M.A., took place in England. All of his major theoretical work took place in Oxford, London, and Trieste, far from the mental and other constraints of Muslim Pakistan. One wonders if he had remained in Muslim Pakistan both for his education and his work, would he have accomplished anything like what he did with a solid Western education and Western colleagues and research institutions?

And still worse, 7 of the 12 Muslim Nobels are in the category of Peace, which is the most subjective, even doubtful, of all the prizes. Those who win in Chemistry, Physiology, and Physics are nominated, and judged, by outstanding researchers in those fields. But the Peace Prize is chosen by Norwegians with a left-handed axe to grind. They did, after all, give a Peace Prize to Yassir Arafat, who before Osama bin Laden was the world’s most famous terrorist. They preferred to overlook his monstrous record and to encourage his supposed move toward peace with his signing of the Oslo Accords, which, in fact, greatly favored the Arab side. Anwar Sadat was similarly given a Nobel Peace Prize for agreeing to take back the entire Sinai, which Israel had won in the Six-Day War. Mohammed Yunus shared a prize for fostering micro-loans among the very poor in Bangladesh. Mohamed El Baradei shared a prize for his work as director general of the international Atomic Energy Agency, though the Americans were not always impressed with his work in Iraq and Iran. His judiciousness may be judged from his claim that Israel is the greatest threat to peace in the Middle East.

Other Muslims won their prizes for defending the rights of women (Shirin Ebadi, of Iran), the rights of girls to obtain an education (Malala Yousafzai, of Pakistan) and for taking part in Yemen’s version of the Arab Spring, with special attention to securing rights for women (Tawakkol Karman, of Yemen). In other words, these three women were trying, though they would not wish to put it that way, to change misogynistic aspects of Islam. Tawakkol Karman, incidentally, was a strong supporter of Mohamed Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt. What’s more, she has expressed her admiration for Ahed Tamimi, the mediagenic “Palestinian” defender of terrorists, including her own relatives who took part in planning the Sbarro Pizza massacre.

Given the regimes in Iran, Pakistan, and Yemen whose misogyny they are protesting, it takes courage but does not, I would argue, in any way stand out for the brilliance and effectiveness of their undertakings. Shirin Ebadi has, in fact, admitted that her hope of reforming Iran from within has come to naught, and only regime change, getting rid of the unelected Supreme Leader, and replacing the theocrats with a secular democracy, will have any effect. Malala Yousafzai now lives in London, and travels the world. She’s written a self-regarding autobiography modestly titled I, Malala — she’s a dab hand at self-promotion — but despite her prize, her effect on children’s education in Pakistan appears negligible. As for Tawakkol Karman, the Yemeni civil war grinds on, and she appears now praising the Saudis, then denouncing them.

What about the five remaining Muslim Nobels? Two were awarded in literature. One was awarded to the monstrously prolific Egyptian novelist and chronicler of Cairo’s lower classes, Naguib Mahfouz. If you don’t know the language of the writer you are judging, as literature is above all a phenomenon of language, you must take on faith that he, or she, is impressive enough to be awarded the Nobel Prize. The Swedish Academy, that awards the prize, appears not to have any Arabic speakers in its ranks. The members have accepted the judgment of outsiders who know Arabic and insist that Mahfouz is a great writer. Perhaps he is. Orhan Pamuk, the Turkish writer, was also awarded the Nobel in literature, and he has been counted as one of the “Muslim” Nobels. But Pamuk himself seems to reject that label, describing himself as a Cultural Muslim who associates the historical and cultural identification with the religion while not believing in a personal connection to God. A “cultural Muslim” is not a Believer; the phrase allows one to disarm critics who might all one, dangerously, an apostate, and Orhan Pamuk is clever enough to avoid that. But how many Muslims would call someone who does not believe “in a personal connection to God” a real Muslim? Pamuk grew up in a very secular Turkey, pre-Erdogan; he’s never given any sign of interest in, or affection for, Islam. Should he really be counted as a Muslim Nobel winner?

Now we come to the three scientists who are claimed as Muslim Nobel winners. One is Ahmed Hassan Zewail, who received a Bachelor of Science and Master of Science degrees in Chemistry from Alexandria University before moving to the United States to complete his PhD at the University of Pennsylvania. After completing his PhD, Zewail did postdoctoral research at the University of California, Berkeley, supervised by Charles Bonner Harris. Following this, he was awarded a faculty appointment at the California Institute of Technology in 1976, and he was made the first Linus Pauling Chair in Chemical Physics. He became a naturalized citizen of the United States on March 5, 1982. Zewail was the director of the Physical Biology Center for Ultrafast Science and Technology at the California Institute of Technology.

In other words, all of Zewail’s graduate work was done in the United States. His doctorate was obtained from the University of Pennsylvania. He did postdoctoral work at the University of California, Berkeley. Then he become a faculty member of the California Institute of Technology, where he remained ever since. He is Egyptian by birth, but completely American in his scientific formation. The resources he relied on, and the mental freedom he enjoyed to pursue his research — these were to be found in America, not Egypt.

Still, he was born and remained a Muslim, though apparently not particularly observant.

The third, and final, Muslim scientist to win a Nobel is Aziz Sancar, a Turkish-American: Ph.D. at University of Texas at Dallas. Then he spent five years at Yale, and then moved to UNC/Chapel Hill, where he has remained ever since. He may be a Muslim for identification purposes, but he is clearly secular. He donated his original Nobel Prize golden medal and certificate to the mausoleum of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, with a presidential ceremony on May 19, 2016, which was the 97th anniversary of Atatürk initiating the Turkish War of Independence.

So he’s clearly an admirer of Ataturk, who did everything he could to constrain the practice of Islam in Turkey, shutting down mosques those clerics were not submissive, giving women the right to vote, encouraging Western dress, having the Qur’an translated into Turkish, along with a translated Qur’anic commentary, or tafsir, so as to limit the influence of the retrograde Arabs, and to better monitor what went on in mosques and madrasas.

Ataturk made his contempt for Islam clear: “This theology of an immoral Arab [presented as Islam] is a dead thing. Possibly it might have suited tribes in the desert. It is no good for a modern, progressive state. God’s revelation! There is no God! These are only the chains by which the priests and bad rulers bound the people down. A ruler who needs religion is a weakling. No weaklings should rule! I have no religion, and at times I wish all religions at the bottom of the sea. He is a weak ruler who needs religion to uphold his government; it is as if he would catch his people in a trap. My people are going to learn the teachings of science.”

Another remark by Ataturk about Islam was even more ferocious: “Islam — that theology of an immoral illiterate Arab bedouin — is a decaying corpse that is poisoning all of our life.”

By leaving his Nobel medal and certificate at Ataturk’s mausoleum, Aziz Sancar was signalling his deep admiration for Ataturk (and, no doubt, also his distaste for Erdogan). This tribute strongly suggests to me that he is not a Believer, but merely a Muslim-for-identification-purposes-only Muslim.

It’s fascinating that three of these Nobel winners have been the object of attacks meant to kill them. Anwar Sadat was murdered by a member of Egyptian Islamic Jihad, for making a peace treaty with Israel, the very thing for which he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, and by which he won back the entire Sinai. Naguib Mahfouz was stabbed several times in the neck by a Muslim because of his support for Sadat’s peace treaty with Israel and because the attacker found his works insufficiently Islamic, but Mahfouz recovered. Malala Yousafzai was shot in the head by a member of the Taliban for daring to promote Western, that is, non-Islamic — education. She, too, recovered.

So let’s sum up, beginning with the initial figure of 12 Muslim winners of Nobels. Of the seven peace winners, all but one (Shirin Ebadi) shared their prize with others. Arafat, Rabin, and Peres shared the prize for the Oslo Accords. Anwar Sadat shared the prize with Menachem Begin for the Camp David Accords. Mohammed Yunus shared the award with the Grameen Bank. Mohamed el Baradei shared the award with the IAEA (the International Atomic Energy Agency) that he headed — it seems the Nobel Committee wanted to send a message of support to El Baradei because of American unhappiness with him. Tawakil Karman shared the Nobel that was jointly given to her, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, and Leymah Gbowee, “for their non-violent struggle for the safety of women and for women’s rights to full participation” in society. Malala Yousafzai shared her prize, given for work on promoting children’s rights, especially education, with Kailash Satyarthi.

By my count, there is only one undeniable Muslim Believer, Ahmed Zuwail, among the science Nobel winners. And there is only one undeniable Muslim Believer who has won a literature Nobel. That means there have been nine, not twelve, Muslim Nobels, seven of them in the doubtful category of Peace. How seriously can one take an award that is given to Yassir Arafat? (Or to Barack Obama for “extraordinary efforts to strengthen international diplomacy and cooperation between peoples”?)

The statistics on Muslim Nobels are thus even less impressive than we have been led to believe.

Here’s a question for study and discussion: why? Why are there so few Muslim Nobels in the subjects that really count — the sciences? The three science winners received almost all of heir education in the West, enjoying in their work the mental freedom that only the West, and not their countries of origin, could supply. Isn’t it plausible that there is something about Islam itself, its deep suspicion and discouragement of free and skeptical inquiry, while the habit of mental submission is encouraged, that accounts for this? Could it be that all the time and mental energy that so many Muslims devote to learning the Qur’an by heart, some even memorizing the whole thing in order to attain the condition of hafiz, takes away from time that might be spent not on memorization, but on comprehension, analysis, discussion? Is it possible that Islam stunts mental growth? Look at the confusion, illogicality, and hysteria of so many Muslim spokesmen, television guests and hosts, now on permanent view at www.memri.org. How many of us would wish our children to acquire what passes for an education in Muslim lands? Is it possible that, in addition to all its other unattractive features, Islam stunts mental growth?

First published in Jihad Watch.