By Theodore Dalrymple

When I bought Prince Harry’s memoir, Spare, I felt obliged to explain myself to the young man at the bookshop counter. I did not want the book for myself, I said—it was not the kind of thing that I would normally read—but I had been asked to review it. From his reaction, he seemed to have heard such an apologia before. I do not think that he believed me, though it was true.

When I bought Boris Johnson’s memoir, Unleashed—at 772 pages, even longer than the bloated Spare—I felt something similar. I did not buy it at the bookshop around the corner in the town where I live, but at the chain-store stationer farther away. There, the check-out was automated: I did not have to make any excuses. And I had brought a tote bag with me to ensure that no one in the street on my way home could see the book.

Both books were piled high in the stores, but Spare was discounted 50 percent from its cover price, whereas Unleashed was marked down by only a third. To my chagrin, when I went to the supermarket later that day, I saw that it was going for nearly 50 percent off. Evidently, Unleashed was not selling as well as the publisher expected.

It was a curious thing not to want to be seen in public with Boris’s book, as if it were pornography. Though I am by no means a fervent admirer of his, neither does he arouse in me the fury that his very name, picture, or voice is now likely to arouse in the more conspicuously right-thinking portion of the population.

In fact, in the days when he was editor of the Spectator, for which I wrote a weekly column, he always treated me well, and, on several occasions, I found him amusing company at lunch. He exuded enjoyment of life, and, like Falstaff, he was not only witty but also a spur to wit in others. He laughed at my jokes, and it is hard to dislike a man who laughs at your jokes. Unlike many celebrities, he was no monologist and quickly inspired affection and loyalty. Years later, when asked about him on the radio, I refrained from saying anything critical, though I’d had no contact with him for some time and already had my reservations.

I also have reservations about political memoirs as a literary genre. They are bound to be self-justificatory, in a way that ordinary autobiographies are not; and the last that I had read, those of one of Boris’s predecessors as prime minister, David Cameron, were so dull that reading them was like eating a dish of sawdust. The memoirs of the deputy manager of a provincial bicycle shop might have been more exciting. If Boris was larger than life, Cameron was smaller. At least, I thought, Boris’s memoirs would be more entertaining than Cameron’s, and I was right. (It is surely significant that one thinks of Boris as Boris and Cameron as Cameron; in fact, there is only one Boris in the world.)

Boris writes breezily, and often with a near-adolescent facetiousness that either amuses or irritates. His intellectual seriousness, as against his evident intellectual capacity, has always divided observers—whether, deep in his soufflé of lightheartedness, there lies a suet pudding of gravitas trying to get out. Is his apparent frivolity a mask covering a deep, sincerely held, political philosophy?

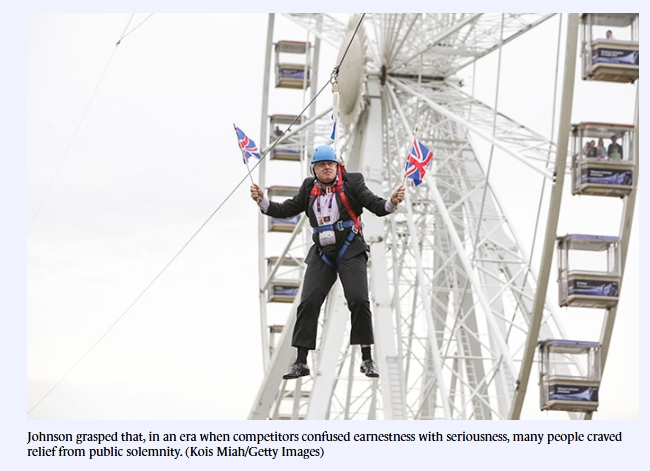

All his life, I surmise, he has been acutely aware of his exceptional ability. Early on, though, he was fired by an ambition to climb the greasy political pole. Standing out was essential, and his light blond hair helped him physically in this regard. (As there is only one Boris, so there is only one coiffure like his.) He also grasped that, in an era when competitors confused earnestness with seriousness—and were consequently dull—many people craved relief from public solemnity. While his rivals avoided jokes for fear of offending (given the modern thirst for taking offense as a badge of moral superiority), Boris took the pragmatic view that you cannot please everyone all the time. This freed him from the tyranny of being bland and earnest. Recognizing that most people enjoy a laugh, he wielded good-natured humor to say the unsayable, often entertaining even his opponents.

He became jocular to avoid the trap of earnestness and solemnity, which are so often boring and usually accompanied by intellectual vulnerability: indeed, earnestness is often a smokescreen for such vulnerability, a substitute for real intellectual solidity. Where such earnestness is prevalent, seriousness and hypocrisy become coterminous, so that generalized cynicism results.

That such boring earnestness is a real, and not an imagined, danger is shown by the fact that Boris himself becomes almost a bore when he tries in the book to be passionately serious—on women’s education, for example, or climate change. He begins to sound like a preacher or a career bureaucrat who has found in a good cause a source of permanent lucrative employment:

The campaign [for female literacy] grew. We had literature, pamphlets, stickers. I appointed a special envoy for female education. I felt it was a good campaign, the right campaign, and I would bring it into every problem that we were addressing.

No apparatchik could have put it better, and he continues: “as I learned my job as foreign secretary, I started to think . . . gender-based prejudice was not in fact so rare, and that this disastrous hostility to female education was the biggest of all the impediments to human improvement.”

He titles his chapter on climate change “Saving the Planet.” When his own mask slips, then, he seems as vulnerable to utopianism as any young student of today. If female education and low net energy consumption were the keys to human betterment and survival, North Korea would be a model to follow.

Jocularity poses its own problems, just as earnestness does. How does one read someone who tries so insistently to be funny? What does he truly think? Constant good humor creates its own type of anxiety: the recipient fears appearing foolish if he fails to catch the joke, taking literally what is—or might be—meant ironically. If he is never sure how seriously to take what is said, he feels like a man walking over ice in leather-soled shoes: focused more on not slipping than on reaching his destination. That is, he concentrates more on deciphering the joke (if it is one) than on addressing the matter in hand.

For someone seeking always to be amusing, the dread of failure also arises, for telling a joke that falls flat is an excruciating social experience. Boris implicitly acknowledges this when he describes an awkward speech he gave to the Confederation of British Industry, an association for the directors of large companies. Into his speech he dragged references to Peppa Pig, a children’s cartoon character of which his audience might not have been aware. He got the references muddled anyway, so that the speech caused people to wonder (in some cases, solicitously) whether something was wrong with him—whether he might have suffered a stroke, for example. The episode is sufficiently well described in Unleashed that one feels, and sympathizes with, the embarrassment that Boris must have suffered.

Of course, Boris can sometimes be extremely funny. He tells the story of an official lunch for then–Colombian president Juan Manuel Santos in London. (Britain is one of the largest foreign investors in Colombia and has helped train its armed forces.) The president, boasting of the natural beauty of his country, noted that Colombia had 40 types of frogs. “That’s nothing!” said Boris. “When I was mayor of London, we had 400,000 frogs—in fact, we had more frogs in London than in the whole city of Bordeaux.”

Theresa May, the prime minister at the time, “goggled at her plate.” There was, as Boris admits, a ghastly silence, until President Santos got the joke and laughed, though not wholeheartedly. But the joke is funny—my wife, who is French, laughed at it—and Boris meant it neither maliciously nor xenophobically, as po-faced critics would now maintain in order to prove their cosmopolitan credentials. It is obvious, however, that Boris, a patriot but not a foaming nationalist, was proud that London hosted so many French that it is now one of the largest Francophone cities in the world.

But was it wise to say such a thing? Boris, after all, was not speaking in a private capacity but as the representative of his country. On the other hand, the joke was harmless, and the elimination of humor from public life is perhaps a greater danger than female illiteracy. It is much harder for truth to prevail where humor is proscribed.

Boris is sometimes verbally inventive. Shortly after he claims not to dislike his predecessor May, he calls her “Old Grumpy Knickers,” and one can’t help laughing. It is an insult, yes, but somehow not completely ill-natured. It is not full of hate, as so many insults are today; it is more Dickensian than Marxist.

The problem of the trueBoris nevertheless remains. Andrew Gimson, a British journalist, tells a seemingly trivial—but disturbing—story in his 2022 book, Boris Johnson: The Rise and Fall of a Troublemaker at Number 10. Though a story at secondhand, it captures, if true, the worries that many have about the former prime minister.

One day, Gimson’s informant sees Boris emerging from the elevator in a conference center near the Houses of Parliament. Boris is on his own and has another meeting to attend; as he emerges, he looks at himself in a mirror. He musses up his hair, and then pulls his shirt from his pants, so that it is partially untucked. Thus, he has an image either to make or to preserve, and to project: that of someone unconventionally scruffy and indifferent to—even above—respectable appearance.

There are scruffy people in the world who are genuinely indifferent to their appearance; it never occurs to them to be otherwise. But just as the true eccentric acts not in order to stand out but because his behavior is natural to him, so the self-consciously scruffy person is far from indifferent to his appearance. He has merely inverted the usual value placed on smartness, marking himself off from the herd. If this is a role that he’s playing, in what other respects might he be doing so? Are his convictions merely another part of the performance? Can a man be sincere in one thing, while bogus in another?

The extent to which the phenomenological Boris is the real Boris—or whether there even is a real Boris—has long been a topic of middle-class dinner-party debate in England. The question raises a deeper philosophical puzzle: Is there ever a “real” person, as distinct from the apparent one? In this way, Boris torments intellectuals, in particular, stirring up a hornet’s nest of undecidable questions.

Gimson recounts something more damning. In 2006, before Boris’s premiership was even a distant prospect, Gimson wrote another book about him—at first, with Boris’s enthusiastic support. Boris, though, soon had second thoughts, perhaps because, like anyone, he had things to hide. He reportedly offered Gimson £100,000 to abandon the project.

Assuming that the story is true (and, as far as I know, Boris has not denied it), the offer was dishonorable—though not a crime—and revealed poor judgment of character, a bad trait for any leader. I knew Gimson a bit when he was younger, and if ever there were someone, modest and polite as he was, whom it would be futile to try to suborn, it was he. Such an offer would likely make him more determined to do what the suborner sought to prevent. Worse still, Gimson was not a visceral Boris detractor; he acknowledged Boris’s extraordinary gifts and better qualities, including his genuine desire for others to enjoy themselves. (Boris, far from denying his privileged birth, played up to it—but he was no snob. His amiability gave him a remarkable ability to connect with anyone.)

Boris’s poor judgment regarding the character of those around him—and whom he chose to surround himself with—may have stemmed from his unshakable self-confidence. He seemed certain that no defeat was permanent, that nothing lay beyond his ability, and that his prominence was unassailable, whatever his actions. While he appears free of the petty malice, envy, and spite that infect the lifeblood of the political spirit (to borrow from Milton), this flaw proved costly. The only bitterness in his memoir is not directed at political enemies (his assessment of Prime Minister Keir Starmer as a kind of human bollard, though accurate, lacks venom) but at former allies and advisors, whom he once considered friends.

Among the most prominent is Dominic Cummings, Boris’s former chief advisor and architect of the Vote Leave campaign before the Brexit referendum. A clever disrupter of received ideas, contemptuous of the British establishment, and seemingly proud of his image as an un-house-trained rottweiler, Cummings became embroiled in a scandal during the Covid lockdown, appearing to break rules that he seemed to believe applied only to lesser beings. Against public sentiment, Boris supported him, only to discover later that Cummings had been plotting against him, leaking unflattering information to the press. Boris exacts his revenge by barely mentioning Cummings in his memoir, treating him as an insignificant figure. It is a feline kind of revenge—one that non-British readers might struggle to appreciate.

What ultimately brought Boris down was not any grave policy failure but a series of relatively trivial incidents, at least by the standards of world events. Alas for him, politics is not only local but often trivial, and Boris discovered too late how many enemies he had amassed within his own party. In one case, he supported a minister, despite strong evidence of improper lobbying; in another, he failed to take allegations of homosexual groping by a parliamentary official seriously, despite knowing of them. Ministers resigned, and Boris ultimately found himself unable to form a government.

Boris does not claim to be faultless, but his self-reflection rarely runs deep. When criticizing himself, he reminds me of Dr. Chasuble from The Importance of Being Earnest: “Charity, dear Miss Prism, charity! None of us are perfect. I myself am peculiarly susceptible to draughts.” Boris casts himself as a naïf, failing to appreciate that the House of Commons is part goldfish bowl, part piranha tank. Yet is it truly credible that a man who spent 30 years as a political journalist so misunderstood the rules of the game?

How will history—that is to say, those who write history—judge Boris Johnson, and what of his own future? Will he be seen just as a mountebank and an opportunist, who rode a wave of discontent to assuage his own demanding, not to say imperious, ego? To return to the question: Behind the frivolous facade, were there just layers of frivolity ad infinitum, or was there a bedrock of serious intent?

I find it difficult to answer. Again, it is hard to be too damning of a man whom one has met and liked. That was, after all, why George Orwell did not want to meet the authors of the books he reviewed. At the same time, I understand those who splutter at the mention of his name.

As to Boris’s future, I think it would be a mistake to write him off. Public memory is short, and at the next election, in 2028, he will be only 64, by which time, if he continues his present trajectory, Keir Starmer will be the most reviled man in recent British history. Boris will be able to pose again as the only way through an impasse: I got Brexit done; now, I will remove Starmer!

First published in the City Journal

3 Responses

Never trust a man who combs his hair with an eggbeater.

“The memoirs of the deputy manager of a provincial bicycle shop . . . ”

A benchmark that deserves to be widely referenced and tested!

From this side of the pond, Boris’ leadership was mostly about his hair. He pretty much neutered Brexit.