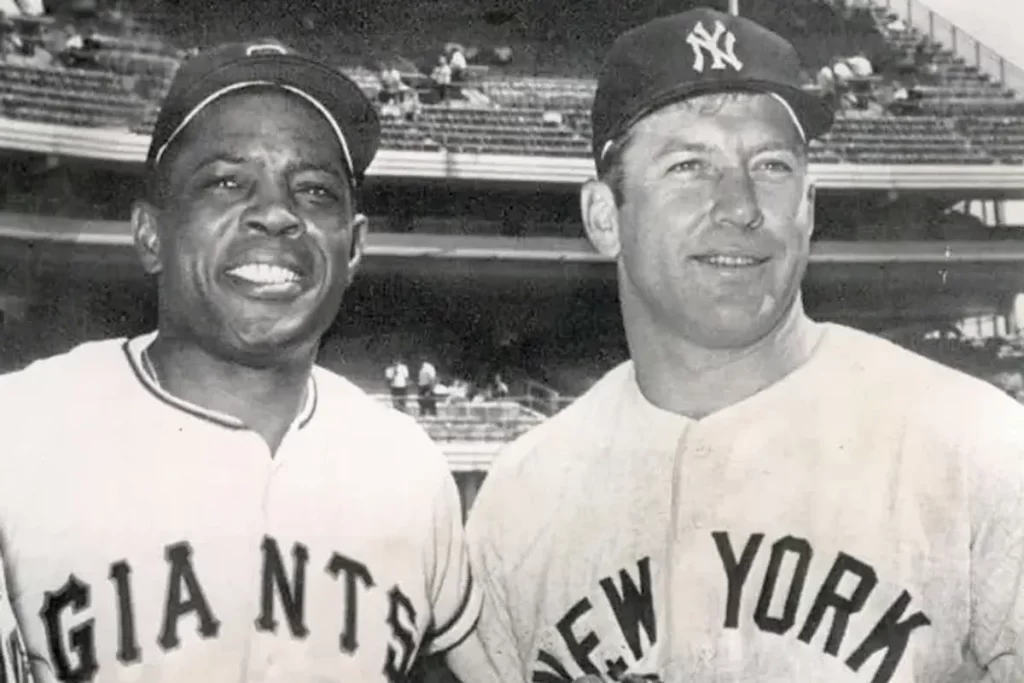

The Idle Contrarian: Mantle v. Mays

by James Como

You’re right: contrary to a narrow consensus, from the early Fifties to the early Sixties – for Mantle who, playing with wanton disregard of his own body suffered many injuries that required leg-wrapping from hip to toe, that’s just about ten years of at-bats (discounting bases on balls, which are not counted as at-bats) – it is no contest: Mantle ruled the game. Some little-noted context will help.

Along the way I will not call special attention to the $12.6 million dollars recently paid for a Mickey Mantle baseball card, nearly twice as much as the nearest competitor (Honus Wagner, the greatest shortstop of all time): Mays is not on the list of the top five; nor to the fact that more Yankee teammates named their progeny ‘Mickey’ than Giants teammates named theirs Willie (which, as far as I know, is zero).

I dismiss those two distractions, and two others. First, sizzle is not steak; second The Catch, so-called, made by Mays in Game One of the 1954 World Series against the Indians, though visually spectacular and rightly acclaimed as wonderful, is not as great as the catch made by Mantle in the 1956 World Series, thus saving Don Larsen’s Perfect Game – the only no-hitter, let alone Perfect Game, ever pitched in the post-season.[1]

Allow me to expatiate.

Black players were finally able to bring their brand of excitement to Major League baseball; for example, Jackie on the bases, Mays with his basket catch and his (deliberately loose-fitting) hat flying off, Vic Power with his unprecedented one-hand play around first base, and others. Now, sizzle is fun, but it’s not the steak. Mantle and Mays – especially Mantle running and swinging: for a long spell there was none faster than the Commerce Comet and his homers brought about the term “tape measure job” – had both, but the SMF (the Sizzle Magnifying Factor) has gone to Mays and thus has inflated the perceived quality of his play (as it has for Ali in the ring).

As for The Catch. It, like Mays himself, was a wonder; it is not my intent to diminish his greatness but to bring to it some perspective. Getting to the ball to make an over-the-shoulder catch four-hundred-plus feet from home plate is the marvel, but: 1/ others could have gotten there; Richie Ashburn (talk about neglected!) of the Phillies, the greatest center fielder of his day, could have, and 2/ the catch itself is nondescript; the ball fell into the glove, no reach, no snatch, no real interception. It had expended its energy and simply alighted.[2]

Mantle’s catch, on the other hand, required enormous speed into the vast reaches of Death Valley, as left-center field in the old Yankee Stadium was called. Mantle was dashing at full speed, a speed that no other fielder could match, and he had to make a back-handed interception of a still-screaming line drive. Backhanded. I would argue that no other centerfielder would have made that play. And, let us not forget, no other superb catch in the history of baseball was more consequential.

Both men won three Most Valuable Player awards; a recent writer (a self-professed Mays fan when growing up) allows that the numbers say each deserved seven such awards. Certain numbers, though, suggest Mantle has the edge, numbers that, these days, the experts claim matter much more than people realized in the fifties: context.

Mays’s best year was not as good as Mantle’s three best (one of which won for him the rare and prestigious Triple Crown). Or take that dreaded rally killer, the double play. Mantle hit into 113, Mays 251: Mantle was the rally, Mays the killer. Or take stolen bases, of which Mays had 338, Mantle 153. Of course, one asks, why would anyone on the power laden Yankees bother to steal a base? But then we have the number of caught stealings: Mantle 38, Mays, 103 – twice he led the league in that statistic, caught stealing. Mays’s success rate was 76.5%, barely enough to justify an attempt, Mantle’s success rate was 80%. In other words, when you needed a base, Mantle could get it, not necessarily with Mays.

Of course Mantle struck out a lot, though not by contemporary standards, but he got lots and lots of bases on balls: 1710 Ks (strikeouts) to 1733 walks. Mays had 1535 Ks, 1436 walks. Notice anything revealing, that these days really matters? That’s right: Mantle had more walks than strikeouts, Mays fewer. The point? Mantle’s OBA – on base average, now considered a key statistic – a was 42%, Mays’s 39%. Mantle’s is 30 points higher, a phenomenal difference.

Mays was the better outfielder, in fact known as “the arm,” for his peternatural throwing ability, but until a fielder fell on Mantle’s right shoulder (he threw right-handed) Mantle was close. In the mid-fifties both had years of 20+ assists – an extraordinary number of men thrown out on the bases (though neither could quite throw with the spectacular Roberto Clemente).

A bit of trivia. When Roger Maris, batting third in the lineup, hit his record-breaking sixty-one home runs in 1961, he had no intentional bases on balls, a device used to avoid a very dangerous hitter (as is the case with Aaron Judge this year). None. Why? Now just guess who was batting fourth. Why would anyone want to put a man on base with Mantle up next? (Mantle, out of the lineup with an infection the last few weeks of the season, hit fifty-four.) I’ll bring this to a close by noting World Series appearances and victories. With Mantle, the Yankees appeared in twelve, winning seven; the Giants with Mays, two appearances, one win – and yet for that same stretch it is the Giants who had more players enter the Hall of Fame than the Yankees. Who must have made the difference?

QED.

[1] Vic Wertz, the Indian slugger who hit the ball, claimed the catch so disheartened his team that, right there and then, they lost the World Series. My answer is, first, if that’s all it took you shouldn’t have been there in the first place, snowflake, and, second, did you pay no attention to the pinch-hitting of Dusty Rhodes? He is what lost you the Series. By the way, in that Series, Wertz hit .500, was on base nearly 56%, and had a homer, a triple and two doubles. Poor wretch.

[2] If you care to see impossibly great catches by a centerfielder look up Jim Edmonds. Cinematic, yes, but no special effects.