By James Stevens Curl

In the Future of Yesterday: A Life of Stefan Zweig

by Rüdiger Görner

(London: Haus Publishing, 2024)

ISBN: 978-1-914979-10-1 (hardback)

eISBN: 978-1-914979-11-8

391 pp., several b&w illus.

£25.00 $34.95

In my youth I discovered Stefan Zweig (1881-1942) in Covent Garden Opera House in the early 1960s. The occasion was a memorably wonderful performance of The Silent Woman, translated into English by Arthur David Jacobs (1922-96) from Zweig’s Die schweigsame Frau, and set to music by Richard Strauß (1864-1949). After the untimely death of Hugo Laurenz August Hofmann von Hofmannsthal (1874-1929), who had provided Strauß with libretti for Elektra (composed 1906-8, 1st performance Dresden 1909), Der Rosenkavalier (1909-10, 1st performance Dresden 1911), Ariadne auf Naxos (1911-12, 1st performance Stuttgart 1912, then in a second version of 1915-16, 1st performance Vienna 1916), Die Frau ohne Schatten (1914-17, 1st performance Vienna 1919), Die ägyptische Helena (1922-3, 1st performance Dresden 1924), and Arabella (1930-2, 1st performance Dresden 1933), the composer wrote that never had a musician found such a helper and collaborator, and that nobody could ever replace the great Austrian writer, a man of incredibly refined sensibility and high intelligence. Strauß received the final version of Hofmannsthal’s libretto for Arabella at his home in Garmisch-Partenkirchen in 1929, but Hofmannsthal was already dead, so never saw Strauß’s appreciative note of grateful thanks.

Bereft, the composer began a search to find another librettist, and during a conversation with Anton Hermann Friedrich Kippenberg (1874-1950), of the firm Insel Verlag of Leipzig, Zweig’s publisher, asked if the by then celebrated writer might have a text for an opera that might suit him. A lively correspondence then ensued between Garmisch-Partenkirchen and Salzburg (where Zweig then lived in some splendour at Kapuzinerberg 5, from which, as he was later to remark, he was able to see Hitler’s Berghof across the border in Bavaria), followed by an even livelier meeting in the Hotel Vierjahreszeiten in Munich, after which it was agreed that Epicœne or The Silent Woman (1609) by Ben Jonson (1572-1637) would provide a suitable basis on which to base a new work. During that encounter Zweig was astounded by Strauß’s artistic insights and his understanding of the theatre. The German composer was very well read, and could appreciate immediately the possibilities Jonson’s work offered, but by Spring 1932 he had to remind Zweig he had not received a draft of Sir Morosus (as the opera was originally to be called). When he did get what he needed he was delighted, and work began at once on the first sketches, so that by October of that year he was well into the task. By October 1934 the whole score had been completed, and in January 1935 Strauß added the short, light, delicious overture (which he called Potpourri, as if to underscore its French credentials), clearly influenced by Gallic precedent, especially the compositions of Georges Bizet (1838-75).

But Die schweigsame Frau was created during an ominous time in German and European history, and Strauß, immersed as he usually was in the creative process, seemed largely oblivious regarding the dangerous shoal waters lying ahead, for Zweig was a Jew. As it happened, there followed “endless to and fro negotiations” and “humiliating and grotesque party-political caterwauling”, until Strauß was “called into the presence of the Almighty and Hitler informed him personally that as an exception he would allow” the opera to be performed “although it violated all the laws of the new German Reich”.

Unfortunately, Zweig’s name had been omitted from all the posters and programmes, causing Strauß to erupt in fury: furthermore, the composer wrote to Zweig urging him to start on another libretto, and expressed unflattering views on the National Socialist government, but the letter was intercepted by the Gestapo, and Strauß was landed firmly in the proverbial soup, a terrifying position to find himself, given that his own daughter-in-law (on whom he doted) was Jewish, and so his grandchildren too were endangered. Indeed, most of the relatives of Alice Pauline Strauß (née Grab von Hermannswörth — 1904-91) were murdered as a result of the antisemitic barbarities of the Third Reich. Strauß persisted in badgering Zweig, but the Austrian writer, far more aware of the very real nature of National Socialism than was the German composer at that stage, refused, realising the peril in which Strauß was putting both himself and his family. And the dangers were very real: Alice Strauß survived only through luck and sympathetic local officialdom. It was a close-run thing.

However, these terrible details were far from the mind of a young man who was enchanted by what he saw and heard in the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, more than sixty years ago. The performance was conducted by the great Rudolf Kempe (1910-76) and the production was by Franz Josef Dietrich Wild (1922-98), with delightful, scholarly period sets by George Martin Battersby (1914-82), the like of which is almost impossible to find in any opera-house nowadays, when designers and producers seems to want to belittle and besmirch every opera in which they get involved. The singing was wonderful, notably that of Sir Morosus (by a fellow I knew slightly, David Ward [1922-83]), Henry Morosus (Kenneth MacDonald [1928-70]), Morbio (Ronald Lewis [1916-67]), and Aminta (Barbara Holt [who seems to have rather fallen off the radar in recent decades, but she was superb]). The music, especially some of the ensembles, was glorious, under the perfect control of Maestro Kempe (one of the greatest conductors of his generation, in my reckoning, as his tempi always seemed to be extremely well-judged, and the nuances of the scores handled with great subtlety and refined taste). It was one of the best performances of any Strauß opera I have ever heard, and at a time when I was immersed in the writings of Arthur Schnitzler (1862-1931), Richard Beer-Hofmann (1866-1945), Robert Musil (1880-1942), and indeed the whole artistic scene of old Mitteleuropa, it made a huge impression on me, and one that has never dimmed.

Ward [1922-83]), Henry Morosus (Kenneth MacDonald [1928-70]), Morbio (Ronald Lewis [1916-67]), and Aminta (Barbara Holt [who seems to have rather fallen off the radar in recent decades, but she was superb]). The music, especially some of the ensembles, was glorious, under the perfect control of Maestro Kempe (one of the greatest conductors of his generation, in my reckoning, as his tempi always seemed to be extremely well-judged, and the nuances of the scores handled with great subtlety and refined taste). It was one of the best performances of any Strauß opera I have ever heard, and at a time when I was immersed in the writings of Arthur Schnitzler (1862-1931), Richard Beer-Hofmann (1866-1945), Robert Musil (1880-1942), and indeed the whole artistic scene of old Mitteleuropa, it made a huge impression on me, and one that has never dimmed.

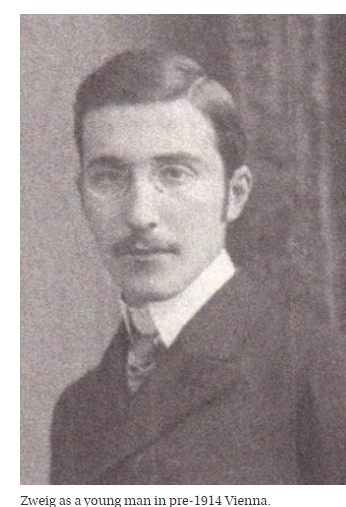

Zweig was born into a wealthy Austro-Jewish family connected with interests in banking and industry: there were many such assimilated Jewish families well established in the old Dual Monarchy (called by Robert Musil “Kakania”, because everything was described as “Imperial and Royal” [Kaiserlich und Königlich]), although underneath the seemingly well-ordered surface anti-semitism always seethed, and was starting to be stirred up again, prompted by Vienna’s Bürgermeister, Karl Lüger (1844-1910), who otherwise was responsible for tremendously impressive improvements to the fabric of the city, its infrastructure, amenities, and hygiene. One of his finest achievements was the creation of the huge Zentralfriedhof (Central Cemetery): he lies in the crypt of the stupendous church of St Karl Borromäus (1908-10), designed by Maximilian Hegele (1873-1945), which dominates the main axis of that great cemetery.

The uneasy, perhaps equivocal, position of Jews, no matter how successful they might be (or perhaps because of that success), began to impinge and disturb many within the Dual Monarchy, to the extent that Kaiser Franz Josef I (r.1848-1916) refused several times to agree to the appointment of Lüger (whom the ageing Emperor and King loathed) as Bürgermeister, perceiving in him dangerous tendencies that could badly damage the stability of His Majesty’s realms. An impecunious student living in Vienna at the time, was profoundly influenced by Lüger’s views: his name was Adolf Hitler (1889-1945).

The phenomenal restlessness of Zweig, incessantly travelling, always on the move, with several projects all going simultaneously, was perhaps prompted by an underlying unease, an insecurity despite the apparently stable conditions enjoyed by well-off Jewish families occupying high societal and economic positions in Austria-Hungary. Early in the 20th century Zweig was awarded a Doctorate for his work on Hippolyte-Adolphe Taine (1828-93), and Taine’s work was to influence Zweig’s approach to history and historical biography thereafter, as manifested in his astonishingly prolific output over the next four decades, yet it was an output in which, despite a powerful injection of Gallic flavouring, always lay rooted in the artistic fecundity of fin-de-siècle Vienna before what the French have called L’Apocalypse Joyeuse and Kakania’s total disintegration.

This new publication attempts to provide a life and work through Zweig’s prodigious output: his books included perceptive studies of several other writers, notably Honoré de Balzac (1799-1850), Michel Eyquem, Seigneur de Montaigne (1533-92), and Romain Rolland (1866-1944); insightful assessments of Marie Antoinette (1755-93), Sebastian Castellio (1515-63), Ferdinand Magellan (c.1480-1521), and others; probings into what he saw as “The Struggle with the Demon” (Der Kampf mit dem Dämon) in the lives of Johann Christian Friedrich Hölderlin (1770-1843), Bernd Heinrich Wilhelm von Kleist (1777-1811), and Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (1844-1900); and a stunning range of translations. Zweig’s choices of individuals were interesting. Some of his protagonists came to untimely ends: an Austrian-born Queen of France by Guillotine; a Protestant Humanist by burning at the stake; and a Prussian dramatist by suicide. But what comes through to the reader of Zweig is that consciousness of the past always remained the main anchor for his work, yet some have seen him as a Modernist, which cannot be right as Modernism deliberately ignores, and even wishes to destroy, everything of the past. Zweig believed, as do I, that there can be no future without an understanding and appreciation of the past. I can remember the sense of desolation I felt when I first read his Beware of Pity (Ungeduld des Herzens, literally The Heart’s Impatience, 1939) and The World of Yesterday (Die Welt von Gestern, subtitled Erinnerungen eines Europäers, 1942), in both of which was an almost tangible, infinitely painful mood of regret and terrible loss.

Zweig himself, though an inveterate traveller, a restless soul, became a refugee when he was obliged to finally leave his beloved Austria before the Anschluß of 1938. He spent some time in England from 1933, first in London, then in Bath, where he had decidedly mixed feelings about his new place of residence, and clearly felt uncomfortable. Matters did not improve as war again loomed large, and he and his second wife, Elisabeth Charlotte, née Altmann (1908-42), who was born in Katowice (Katowitz, in what was then Austrian Poland), crossed the Atlantic, ending up in Brazil.

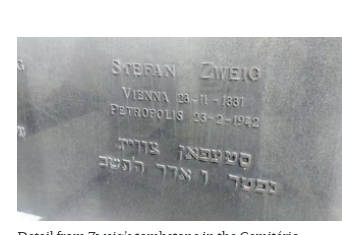

Görner’s book is not a conventional biography, and is based largely on Zweig’s literary works from which the Austrian’s views on Europe, Zionism, the world order, and much else have been extracted. Unfortunately this has meant that chronology is confused, and there is a great deal of leaping about in time, backwards and forwards, forwards and backwards, and factual information is often difficult to find as a result of these gymnastics. There are oddities too: the hugely important artistic collaboration between Strauß and Zweig for Die schweigsame Frau is only mentioned in passing, almost dismissively, and not given any real attention, while Zweig’s apparently ambiguous sexuality (despite his marriages) is not treated in any depth, although the erotic remained important to him, in its many manifestations, throughout Zweig’s career as a writer. There are frequent references to the double suicide of Zweig and “Lotte”, his wife, in Petrópolis, early in 1942, but we are not told how they did it (it was overdoses of barbiturates), and there are some extraordinary clangers, such as reference to the “heroic struggle” of the “new Republic of Ireland” in 1924 and the “Irish President Cosgrave”. In fact, William Thomas Cosgrave (1880-1965) was president of the executive council of the Irish Free State (Saorstát Éireann, as the 26 Counties were called) in 1922, having previously been chairman of the provisional government from August 1921: the Free State did not formally become a Republic until April 1949, when it left the Commonwealth, confirmed in the Ireland Act (12, 13, & 14 Geo. VI, c.41).

This tome has many insights into the complexities of what was a highly sophisticated cosmopolitan character, but it is often marred by some horrible sentence construction and some very dodgy grammar, but the worst thing about it (and this a very serious omission) is that it has no index. What on earth prompted the publishers and author to produce a book with so many cross-references, names, and places without a good, comprehensive index? The lack of such a tool makes the book an absolute pain to use, and infuriates the serious reader.

Görner was not only unaccountably sparing about Die schweigsame Frau, but uninformative on the suicide, hence my attempt to fill the gap with barbiturates. He is also uninterested in telling us what happened to the bodies, so I can also reveal they were entombed in the Cemitério Municipal de Petrópolis, Rua Coronel, Petrópolis, Rio de Janeiro, in plot number 47417. Now this is rather interesting, for as an assimilated, sophisticated, cosmopolitan, well-travelled, wealthy Austrian Jew, Zweig tended to emphasise his Europeanness, not his Jewishness, and stayed largely out of the pros and cons of Zionism. Yet his tombstone, and that of his wife, have inscriptions in Hebrew, perhaps suggesting, in the end, a retreat, even in death, to their mutual roots, for Lotte, too, was Jewish.

What prompted their joint suicide? Having read much, but only a fraction, of Zweig’s work, I am convinced it was loss, longing for their vanished homeland, for an old Europe, savagely destroyed, because the wistfulness, the sadness, the desolation of the disinherited, uprooted from their familiar habitat, come tumbling out of works such as Die Welt von Gestern.

But there is more. The Zweigs, as “enemy aliens”, were very uncomfortable in England, and were fortunate eventually to obtain British naturalisation, but the threat of a German invasion with the horrors that would unleash, were very real in 1940 when they managed to cross the Pond, eventually settling in Brazil. But in January 1942 Brazil severed diplomatic relations with Germany, Italy and Japan, prompting an immediate hostile response, including the sinking of the Buarque, a Brazilian merchant ship, by U-432, and other devastatingly destructive attacks on Brazilian shipping. This led to Brazil declaring war on the Axis powers in August 1942. The unexpected involvement of Brazil in the war doubtless played its part in the decision of the Zweigs to give up and leave the scene without running away yet again. There was another problem for Zweig: in general, German literature, poetry, etc., tend to be grossly undervalued in England, which has always tended to kow-tow to the supposed superiority of France’s contributions to those fields. Even a proposal to put up a Blue Plaque where Zweig lived for a time at 49 Hallam Street, London, was turned down in 2012, and the London Review of Books in 2010 airily dismissed Zweig as the “Pepsi of Austrian writing”, in contrast to the amazing reception his work is having in present-day China, as Arnilt Johanna Hoefle made clear in China’s Stefan Zweig: The Dynamics of Cross-Cultural Reception (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2018).

And there is yet another mighty spectre casting its shadow over everything, and that was the catastrophe of what happened in 1914. Zweig’s “World of Yesterday” was in fact the world of a civilised Europe before the Great War, and he evoked that lost world over and over again in his writings. And if it is true that the Serbian government warned Vienna that it might not be wise for the heir to the Dual Monarchy to visit Sarajevo in June 1914, then what happened later suggests that Vienna might be doubly culpable for the tragedy that destroyed so much and led to the horrors that filled most of the 20th century thereafter.

If Zweig understood that, much could be explained: the knowledge would have been almost unbearable.

First published in The Critic

- Like

- Digg

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

2 Responses

I enjoyed reading this essay.

Zweig’s The World of Yesterday, Memoirs of a European, which I read only a few months ago, told me as much as or perhaps even more than I could wish to know about him. The painful loss of the bright world of his youth, never to come again, permeates the writing in that autobiographical work — I found it difficult to finish and can only imagine that the pain he must have lived with everyday would have been far more intolerable.

I do not understand why he settled in Brazil, of all places, when he might have had a better reception in the US, where, if I recall, he had spent some time just prior.

I wondered about why the US wasn’t a preferred destination.

Like some of my immigrant forebears, the war would make their situation more complicated and ambiguous.

If they’d held on longer, would they have made Aliyah? Maybe Israel probably would have been too foreign as well. The Zweigs couldn’t find a place in this world. Sad story.