The Master of Confessions

a review by Armando Simón

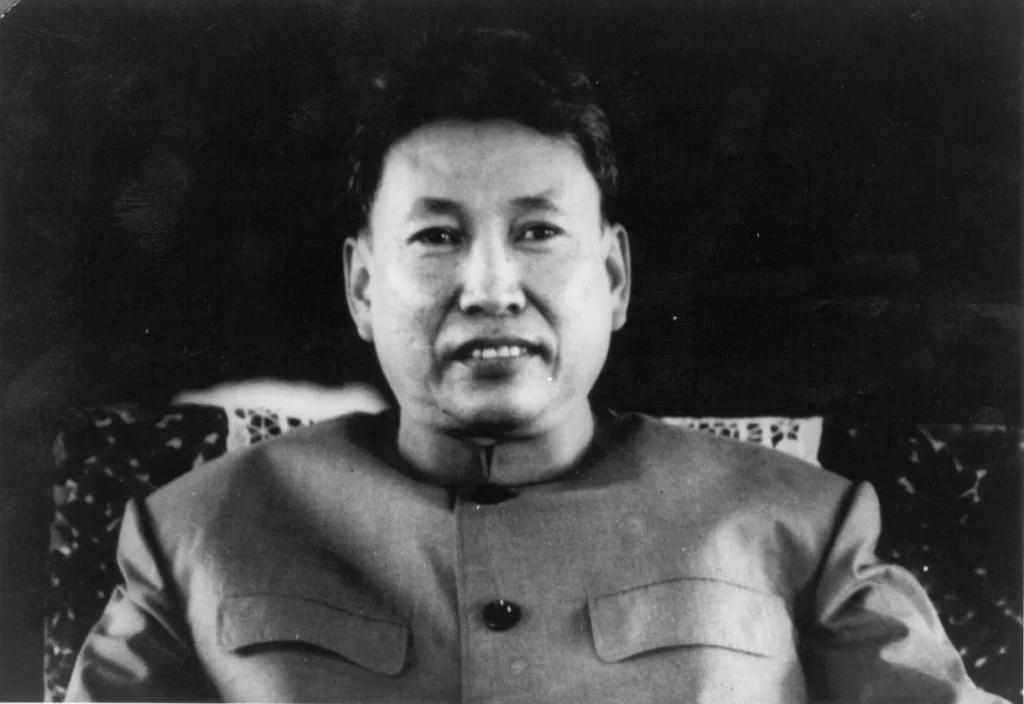

“Better to kill an innocent by mistake than spare an enemy by mistake.”

—Pol Pot, Brother #1

“Paranoia moves at a gallop; it never stops. Nothing appeases the paranoid man.”

—unnamed psychologist at the Court

I can categorically state that Master of Confessions is the best book I have read in several years. The reasons for this book’s importance lies in its wealth of information on my two topics of professional interest, history, and psychology.

The book is written by Thierry Cruvellier, a French journalist who has covered previous war crime tribunals. S-21 was one of the prisons operated by the genocidal Khmer Rouge and was the Cambodian equivalent of Auschwitz. Prisoners were tortured, beaten, starved, drained of their blood until dead. Paramount in their goal was to make them confess, often to accusations that could only have been dreamt by a psychotic, before being executed anyway. If they were going to be executed, regardless of lack of evidence or confession, why insist that the prisoners confess? This is typical of the psychotic mindset of totalitarian fanatics.

Although there were other camps of extermination, S-21’s importance is due to the meticulous archives that were maintained, including the pictures of the prisoners, which were not destroyed when S-21 was abandoned as the enemy approached the capital. The detailed documentation of the victims and of the crimes is what one would expect from pedantic intellectuals, since all but one of the upper echelons of the Khmer Rouge had had a university education.

The fact that the Khmer Rouge elite were college educated yet mandated that all Cambodians who had had education had to be killed is a sick irony. The exception was Ma Tok, Brother #4, the Beria of the movement.

Sometimes Marxist gibberish would be uttered in court, leaving everyone confused.

The Cambodian Eichmann of S-21 was a man named Duch, and the book details his trials for crimes against humanity (Duch is unique of any war criminal anywhere in being repentant for his crimes, unlike Brother #1, Pol Pot, who declared to the end that his conscience was clear). Cruvelllier describes the at times tedious intricacies and splitting hairs of the trial (characteristic of all trials), interspaced with lurid descriptions of the crimes.

At times, the book reads like Darkness at Noon.

So why is this book so important?

First, because there is really so very little knowledge available to the public about the Khmer Rouge and the details of what went on during its brief dominion (less than the Third Reich, longer than Bela Kun’s). Its rule was characterized by hyper-secretiveness, even more so than the usual Communist rule.

There is only one well-known film about that period, The Killing Fields. There is also a lesser-known film, First they Killed My Father. There are also two or three obscure documentaries that require an Indiana Jones to track them down. Compare that to the hundreds and hundreds of films on the Nazis, so many of them that one feels the Nazis are being shoved down our collective throats, so many that many people believe they were the only ones to commit such crimes and are ignorant about the atrocities of the Mongols, the 30 Years War, the Zulus, the Bosnian war, the Armenian genocide carried out by the Turks, the conquistadores in the Caribbean, Stalin’s genocides, the Holomodor, and the Khmer Rouge, and believe that only the Nazis carried out massive mass murders.

At any rate, during the Vietnam War, weapons and troops were coming down through a corridor in Laos and Cambodia and into South Vietnam. Cambodians have traditionally hated the Vietnamese just like the Vietnamese have hated the Chinese. So, the American government encouraged a successful coup. The Cambodian military began attacking the corridor. As a result, the embryonic Communist movement within Cambodia grew exponentially as a guerrilla force which in a few years defeated the army in 1975 and took over the country.

The Khmer Rouge leaders had a philosophy. As is always the case for all the totalitarian movements, the previous society was seen as evil, corrupting, unjust, hierarchical which must be replaced (sound familiar?).

The Communist leaders had an original solution. Since the cities were the center of the previous society, the cities’ population would be emptied out, forcibly removed into the countryside, including hospital patients. The sick and weak were exterminated en route. And because Marxism glamorizes the poor, the peasants and the menial workers, any Cambodian who did not fall into this category, any Cambodian who had education (and, thus, contaminated with wrong ideas), was exterminated: doctors, nurses, teachers, bureaucrats, landowners, businesspeople, lawyers, students, scientists, engineers. Two million people died. The rest were employed in slave labor.

To further accelerate the process, the family unit was broken up. Although everyone was indoctrinated, the focus was on children. They would usher in The New Man. And they indeed turned out to be the most ruthless. Duch stated in court that teenagers were:

like blank pages on which you can easily write or paint…. We took in many young people and trained them to be cruel. We used Communist jargon to normalize extreme situations—that played a big part in turning innocent people into brutes. Their characters changed. Their kindness gave way to cruelty. They became motivated by class rage.

Sound familiar?

Prior to joining the Revolution Duch himself was described by others as being neither a monster nor insane. On the contrary, he was described as gentle and accessible as a teacher who encouraged students.

Karma

A particular characteristic of Marxist and quasi-Marxist regimes in the early stages of rule is the propensity of the ruling elite to kill each other and to go after imagined traitors/dissidents/spies within its ranks. One sees it in the French Revolution with the Jacobins persecuting the Girondists, the Stalinists going after the Trotskyites and the Zinovievs. Not only is this due to the inherent paranoia embedded in the movement, but also in the fact that these totalitarian movements are orchestrated by intellectuals and anyone who has had extensive dealings with intellectuals will testify how vicious, how backstabbing, how splithairing, how intolerant of disagreements they can be (sound familiar?).

And so it is that one year into the establishment of their rule, the Khmer Rouge started going after spies in their rank, the reasons fluctuating from not fulfilling agricultural quotas to not killing enough people who were enemies of the people, to being CIA spies (many had no idea what a CIA was) and, again, the accusations were bizarre. Then, the leadership started turning on each other. Duch saw the teachers who had recruited him into the Revolution go by his prison on the way to torture, confession and execution under his administration. Some of his in-laws were executed. If high officers were killed, so were their subordinates, and so were their children, with a pickaxe to the skull. 50 staff members of S-24 were sent toS-21 and killed. Ultimately, three quarters of the S-21 victims were themselves Khmer Rouge leaders and minions of the regime, along with their families. One day 160 children were executed. Some of his own staff were arrested and disappeared.

Duch knew that it was a matter of time until it was his turn, yet stayed at his post until the Vietnamese were at the gates of the capital, at which point he and other guards ran away. Seven prisoners survived.

Many of those who ordered the killings were ultimately never punished and even went on to obtain positions in the liberated Cambodia, a common occurrence in former Communist countries.

It would be fitting to end this review with a realization that a disillusioned Duch voiced at the trial: “I didn’t know that the Party’s intention was to abolish civilization and man.”

Armando Simón is originally from Cuba, author of Orlando Stories and When Evolution Stops.