The necessary and the unnecessary wars

by Lev Tsitrin

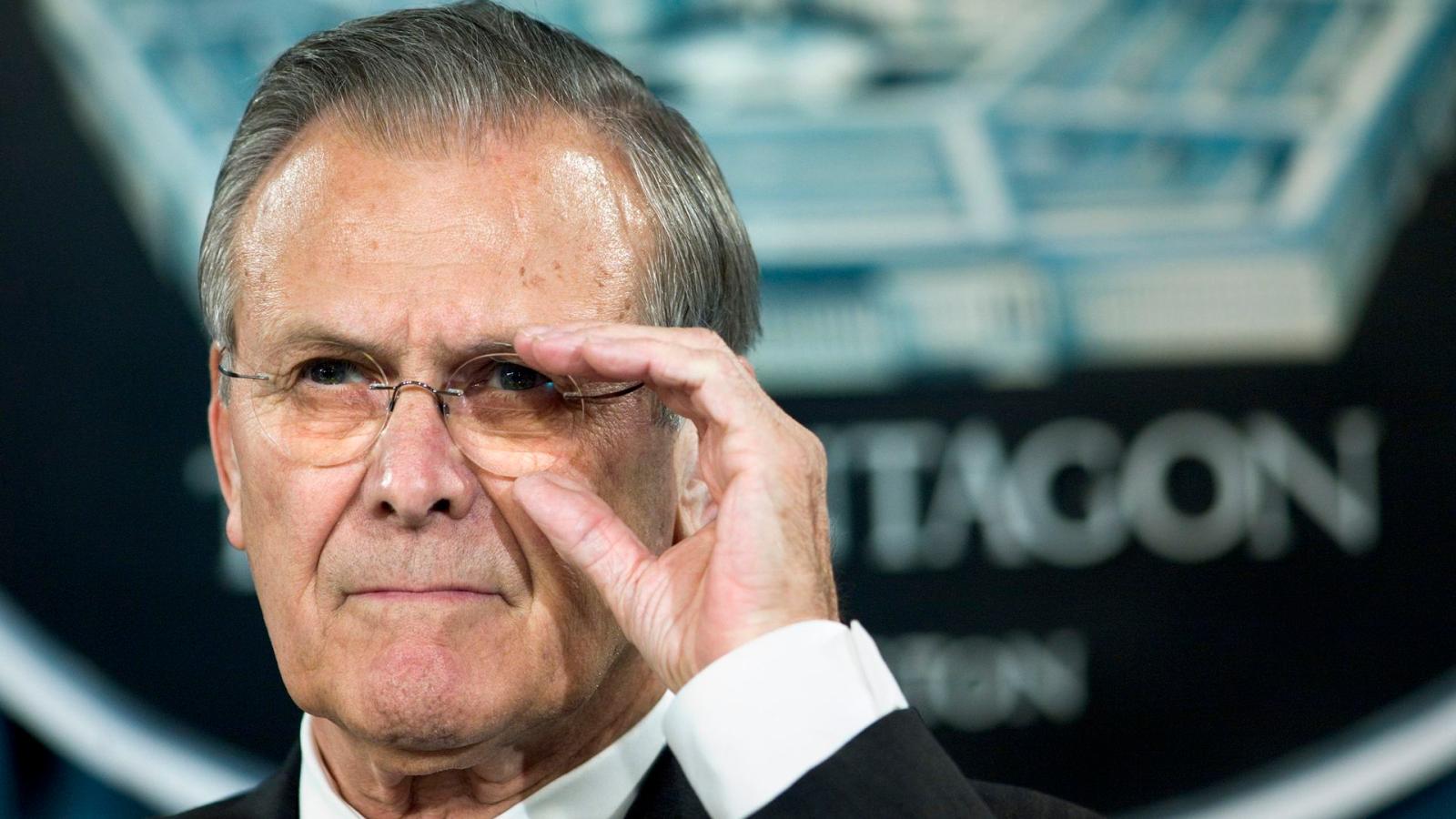

The passing of Donald Rumsfeld, President George W. Bush’s Defense secretary, reignited for a moment the analysis of the Iraq war, and discussions of whether it was, or wasn’t justified, of whether it was fought aright, of whether its goals were realistic, of whether it achieved anything except for dragging America further into the “endless wars” from which President Biden now tries to extricate America via exiting Afghanistan and re-entering the Iran ‘deal” so as to be able to focus exclusively on the treat from the Communist China.

I won’t discuss China or Iraq, but I want instead to look into the general question of the necessity of war.

Is war ever necessary? Or does it have to be avoided at all costs?

A war is destructive and disruptive, and no generation that experienced it welcomes another round. This was the express reason why, in the aftermath of the World War I, the West was willing to tolerate the violations of the Versailles treaty by the Nazi Germany, and tried to appease and accommodate it all it could. Versailles treaty forbade Germany to have the navy or the air force — and yet England agreed to let Germany build “limited” amount of battleships, and no one was particularly worried about German pilots training in the Soviet Union. There was perfect willingness to look the other way at German re-militarization of Rhineland in 1936. On the eve of marching into Rhineland, Goering reportedly got nervous. “Won’t they just swat us like a swarm of buzzing flies?” he wondered aloud. “Not if we buzz loud enough,” was Hitler’s cold reply. Yes, it was a blatant violation of the Versailles treaty, but to oppose Nazi Germany meant going to war — and no one was willing to do that. Peace was far too precious; in fact, Hitler’s most frequently-used word before 1939 was “peace.” European politicians reciprocated. “The alternative is a war” is politicians’ invariable excuse to do nothing in the face of bullying, insolence and aggression.

This was also President Obama’s rationale for the Iran deal. In his mind, Iran’s getting an atom bomb was an inevitable near-future fait accompli, and he wanted to push this eventuality into another administration’s lap, offering Iranians an irresistible “deal”: postpone the making of a bomb for fifteen years, past Obama’s, and the following administration (which he expected to be Hilary Clinton’s), and America will agree to grant Iran’s nuclear effort full legitimacy. Instead of making the bomb illegally now, make it legally fifteen years from now. Those who objected to the “deal” (like Israel’s Netanyahu) were but war-mongers, because in Obama’s mind, only war could prevent the bomb, and just as the Europeans in 1936, the very thought of war was unbearable to him. “Better bomb than bombing” was the battle cry of the Iran “deal” lobby.

Well, looking back, we can see what happened after 1936. Emboldened by his success at proving that European nations were incapable of standing up him, because the ultimate value — peace — was at stake, Hitler went on on a rearmament spree, to be followed by a spree of takeovers — of Austria and Czechoslovakia. He knew all too well that “for the sake of peace” European leaders won’t object — and they didn’t. In mere six years from 1933 when the Nazis took power, Germany went from having no army to speak of, to the most advanced fighting force with the best equipment and military doctrine, which allowed Germany to easily and quickly overtake the continental Western Europe. The sheer immensity of the Soviet Union, as well as colossal shipments of American materiel saved USSR from sharing the same fate. Yet the results of the war were horrendous. The conscientious, good people who wanted to avoid a war in 1936 only invited a much more terrible war, in which over eighty million people died. Not going to war in 1936 when the war was necessary, proved a disaster.

At least the rearmament part of the Nazi story has a close parallel with Iran, even up to its chronology. In 2015 when Obama’s “deal” was signed, there was nary an Iranian missile or drone; by now, six years later, Iran has an immense fleet of highly accurate and deadly drones and missiles. Its leap in uranium enrichment is equally impressive. Its well-armed proxies in Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, and Yemen are encircling Iran’s enemies. And just as was Germany in 1930es, today’s Iran is highly ideological and self-righteous, its fighters assured that their death in battle is a mere transfer to a chick bordello of Islamic paradise. Iran violated plenty of key terms of the “deal” by now, presumably deserving at least the “snapback” of UN sanctions; yet the powers keep trying to pretend that all is well, in the hope of getting America back into this “deal.”

All this wilful blindness for the sake of “avoiding a war” begs a question: are there wars that cannot be avoided, and must be fought? Does “the alternative is a war” mean that one has to muster the courage to confront the enemy, or is it an excuse to avoid — and in reality, merely postpone — doing so? Is it possible that a good, war-opposing person can cause much more death and destruction than the one who relies on the military force to deny the enemy an ability to get stronger? Can the price of not having a war be too high — a future war that is far too terrible to contemplate?

On this sad occasion of Donald Rumsfeld’s passing, I won’t go into the assessment of the Iraq war, of its winners, its losers, and its impact. I will only say this: there are wars that have to be fought. There is death and destruction in any war; those accrued in fighting a war of choice are a tragedy; those avoided by not fighting the war of necessity, result in am unmitigated disaster. That, I think, is the right reflection on the legacy of Secretary Rumsfeld.