by Theodore Dalrymple

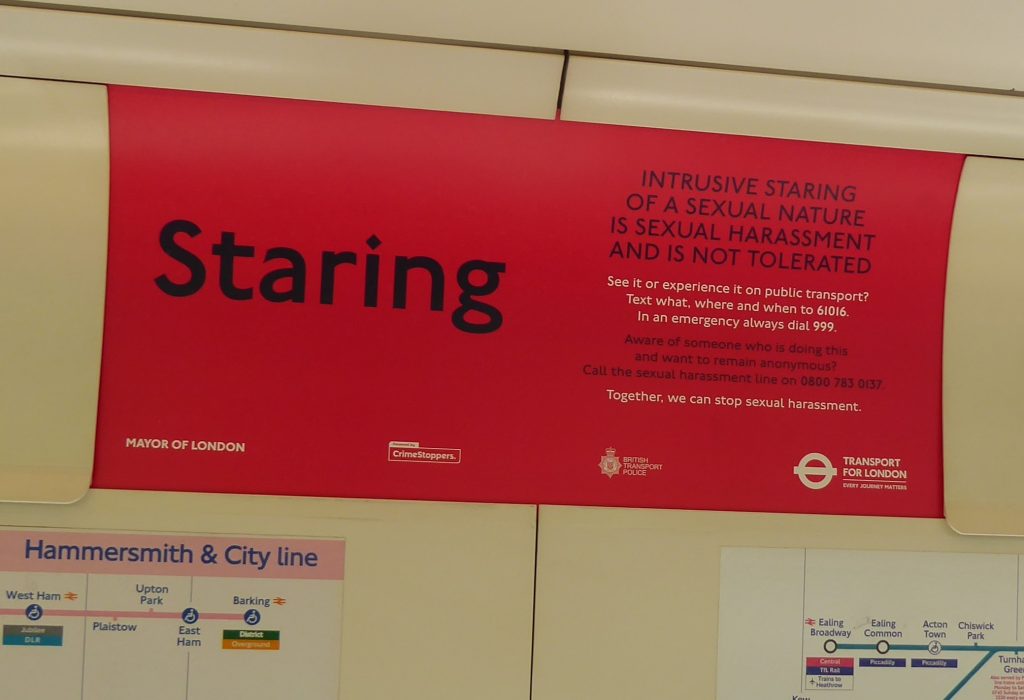

In small things, if one pays close enough attention to them, can often be seen wider trends. One such small thing is a notice that has been posted recently in London’s Underground stations, by order, apparently, of the Mayor of London, the Metropolitan Police, and public transport authorities.

The word “Staring” is printed on a blood red ground in large bold black letters. A legend in smaller, but capitalized, black lettering says:

INTRUSIVE STARING OF A SEXUAL NATURE IS SEXUAL HARASSMENT AND IS NOT TOLERATED.

Then follows the legend, in yet smaller black and white lettering:

“See it or experience it on public transport? Text what, where, and when to 61016. In an emergency always call 999.

“Aware of someone who is doing this and want to remain anonymous? Call the sexual harassment line on 0800 783 0137.”

The last line is supposed to be encouraging:

“Together we can stop sexual harassment.”

It would take a long disquisition to dissect (or in the modern parlance, deconstruct) this notice, and I will attempt in a short space only to point to some of its more sinister features.

No one can doubt that being stared at is an unpleasant experience, and few of us can claim never to have stared. For example, I’m inclined to fix my eyes on someone whom I believe I have met before, but have forgotten his or her name, or where and in what circumstances I met him or her. I catch myself doing this and then lower my eyes.

But what’s the objective correlative of being stared at in a sexual manner? Are you necessarily being stared at in this way if you think you are? Is staring in the eye of the beholder or in that of the beheld? Is it possible to be oversensitive in the matter of being stared at? (A friend of mine pointed out something that I had not thought of about piercings through the nose and other features of the face: They’re so disconcerting that they’re done to avert the gaze of strangers.)

Is it possible to appear to be staring without actually doing so, for example, if one is very short-sighted or even partially blind? And how many seconds of regard constitute staring? Must a leer accompany the staring, and is a leer in the eye of the beholder?

Is it not possible that a notice such as this will call forth the very psychological fragility that it’s supposed ostensibly to assuage? Will not staring—after all, a pretty normal phenomenon—come to be yet another cause for anxiety, as if we lived in the most dangerous of possible worlds? How many stares proceed to sexual assault, let alone sexual murder?

The purpose, or at any rate the effect, of involving authorities in such a swamp of ambiguity, from which endless argumentation is certain to emerge, is to absolve them from their real and genuine duty to protect the public from unambiguous crime, which takes determination, intelligence, and courage, sometimes physical but always moral. If you’re engaged upon the suppression of staring, you will have neither the time nor the energy enough to tackle real malefactors.

The provocation of fragility requires a bureaucracy of defenders to alleviate its consequences. The more fragile people become, the more they will run to the authorities for protection, as children run to their parents when they imagine witches at the window. A fragile population requires protectors, for the fragile by definition are incapable of protecting themselves, for example by confronting or moving away from a starer, but the would-be protectors themselves are cowards who prefer imaginary enemies to real and dangerous ones: thus is the dialectic between fragility and public employment on futile tasks created and maintained.

Perhaps the most sinister aspect of the whole notice is its appeal to anonymous denunciation, again whose main purpose is to create an atmosphere of fear, vulnerability, and mistrust in the public, the very atmosphere that totalitarian regimes love and create. What the authorities want, consciously or subconsciously, is a population whose individual members fear to look at one another and therefore fear to converse, for such a population can’t oppose whatever is imposed upon it. Complete atomization, though without individuality, is what’s being aimed for.

The last line—I’m tempted to call it the last straw—is “Together we can stop sexual harassment.” This suggests, and is intended to suggest, that the authorities and the public are united in their priorities and their goals, and that the former have the latter’s interests at heart, with no interests of their own to pursue.

Needless to say, the notices didn’t appear on the walls by spontaneous generation. In fact, the work involved in producing them must have been considerable. If my experience of a hospital is anything to go by, I can easily imagine the hours of meetings with earnest (though not serious) discussion over the “problem” of staring, the way to tackle it, the wording and design of the posters, and so forth. Perhaps the people involved in these meetings worked overtime, with a sense of urgency, under the misapprehension that activity is work. At any rate, the overtime worked would be an argument in their favor if redundancies ever became imperatively necessary. No one in such meetings would dare to point to the futility of the whole enterprise, for fear of not being, in the words of Human Resources (which mines people as coal miners mine coal), “a team player.” There’s nothing worse in a bureaucracy than not being a team player.

Suppose I think, rightly or not, that someone is staring at me on the Underground in a sexual fashion and I denounce him: What happens then? Does the anti-staring squad get on to the train at the next stop and tell him to refrain henceforward from doing so, or even arrest him if records show that it’s a second offense?

Of course, the people who dreamed up and posted these notices that so seamlessly combine idiocy with nastiness don’t seriously expect many people to read them thoroughly or reflect and act upon them. The message that they convey to the majority is the following: In your hour of danger, we care for you, so re-elect us. But with luck (that is, for the mayor, the police, and the transport authorities) a sufficient number of fragile neurotics and paranoiacs will act upon the suggestions and sow fear like poison gas throughout the Underground.

First published in the Epoch Times.