The Real Meaning of the Midterms: One Country or Two?

by Roger L. Simon

As were many, in the run-up to the midterm elections, I was seduced by the great Red Wave.

I was even beginning to feel guilty that I hadn’t stayed behind to help—a touch anyway—and had moved to bucolic Tennessee.

Maybe I should have gone back to my New York City roots to do what I could for Lee Zeldin, who seemed to be running an intelligent gubernatorial campaign.

But then, the wave never materialized, for whatever reasons, and my window was gone.

I am writing this while much tooth-gnashing is taking place over which party will control Congress, but it doesn’t matter because something else far more important was made clear, if it wasn’t already, and—because of these arduous, monumentally unenlightening—midterms, we are forced to face up to it.

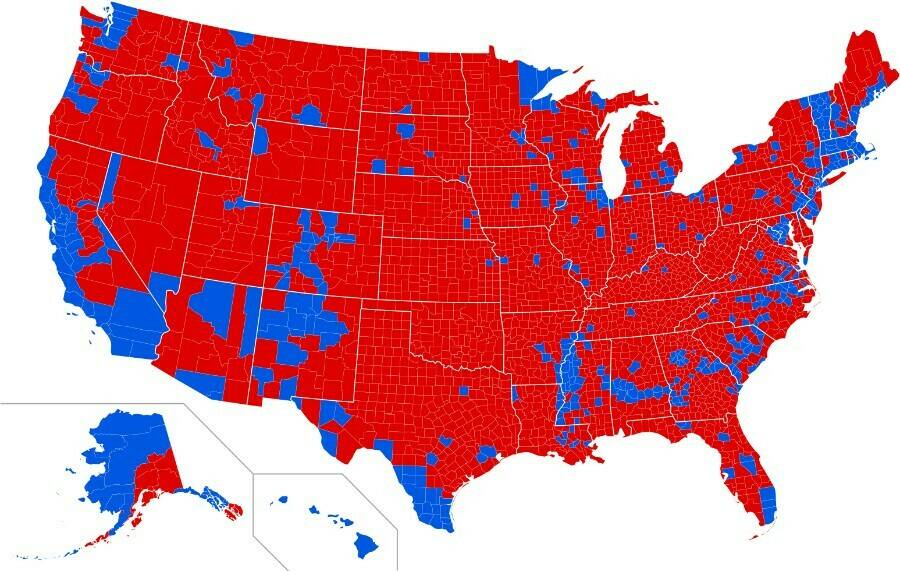

We are now two countries, intractable.

We don’t like each other. We don’t want to talk to each other. We don’t even want to be around each other.

The mass internal migrations to red states from blue states of the past decade show this has long been underway. We are a nation of American Refugees, much as we were once a nation of refugees from other countries. (We are also unfortunately an open border country, but what I am recommending would fix that.)

A recent article by Joel Kotkin—“A Tale of Two Americas”—has a lot to say about this phenomenon that might disturb Democrats, no matter how many electoral victories they may have achieved in the midterms.

“Whether Democrats like it or not, these red-leaning places, not California or New York, are where more Americans plan to settle and start families. Today, blue-state economies, based on tech and finance, generally underperform more blue-collar red economies like Texas, Arizona, Florida, and Tennessee.

“Over the past five years, Raleigh, Phoenix, Nashville, Salt Lake City, and Dallas have grown jobs at a faster rate than Silicon Valley and Seattle—and at double the rate of New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago.”

People like to say that most of this migration is based on taxes—economic self-interest. That’s obviously part of it, but the research I’ve been doing for a book I’m writing about the American Refugee tells me something rather different.

This migration is largely powered by the personalities and beliefs of the migrants themselves. It took more than money to get many of them to move their families across the country—an act of tremendous aggravation and costly in itself. It was an act of love and passion and, in many cases, faith.

They, most of them anyway, are fleeing from progressive blue America to a land they hope and assume will be their new constitutionalist homes, the way the Founders envisioned them.

They want to live in a totally different America, the one they were raised in.

Sometimes, they have been disappointed, but these people are fighters and have no intention of returning to Chicago. And given what is happening, they will soon be joined by many more like them.

The midterms have reminded us for the umpteenth time of what has become increasingly obvious.

E pluribus unum—out of many, one—doesn’t seem to make much sense anymore, not when the many is approaching 350 million or even 400 million.

Maybe it’s time for a serious course correction—perhaps secession at some level. The question is how.

Yes, that’s a very painful thing to contemplate, and, yes, there are many exceptions, many tolerant individuals in our and other cultures who have been trying to overcome our mutual angst, but in nation-building, or, more specifically, maintaining, the time may have come to face the reality that the United States has reached its limit.

But is that a bad thing?

Uncomfortable, of course, possibly excruciating at times. We don’t need Neil Sedaka to remind us that “Breaking Up Is Hard to Do.”

Almost all of humanity has experienced it to some degree on a personal level and a fair number on a historical level as well.

Of course, it wouldn’t be easy—the disruption from all sides would be monumental and we’ll have to work out some mutual defense agreement against China, etc.—and of course, you could fill the comments sections of all the websites in the country with a million objections, serious and picayune, but allow me to inform those commenters of something I’m pretty sure they already know:

History happens—like it or not.

There’s no Roman Empire anymore.