The Strange Phenomenon of Celebrity Endorsement

by Theodore Dalrymple

A celebrity, a friend of mine once said to me, was someone of whom he had never heard. My friend lives a little like a hermit in retreat from the modern world, but for most people, celebrities are like burglars: you don’t have to go to them, they come to you—inescapably, via all sorts of media.

I am, like my friend, indifferent to celebrities, and many of them who are household names are completely unknown to me.

Celebrity has long been the desire of many, but the idea of being recognized as you walk down the street, of having to shy away constantly from prying eyes and from people anxious to take selfies with you, fills me with horror. A French neighbor told me that he was contented though modest; I suggested that he should have said contented because modest.

The social media have no doubt increased the avidity for celebrity in the general population. There’s a lot of money to be made from it, and influencers can suddenly become very rich and famous without any obvious talent or qualification. Of course, for every influencer who succeeds, there are a thousand or more would-be influencers who fail: But success is visible; failure (though far more prevalent) is hidden.

Celebrity is a phenomenon simultaneously of great depth and great shallowness. It’s deep because it tells us something important about mass psychology; it’s shallow for the same reason it tells us how trivial or frivolous are many of our thoughts.

I read recently an article about the similarities between Sam Bankman-Fried and the late Bernie Madoff. Superficially very different, argued the article, they both traded on the seeming complexities of their schemes, which nevertheless were allegedly fundamentally very similar: paying old clients with new clients’ money.

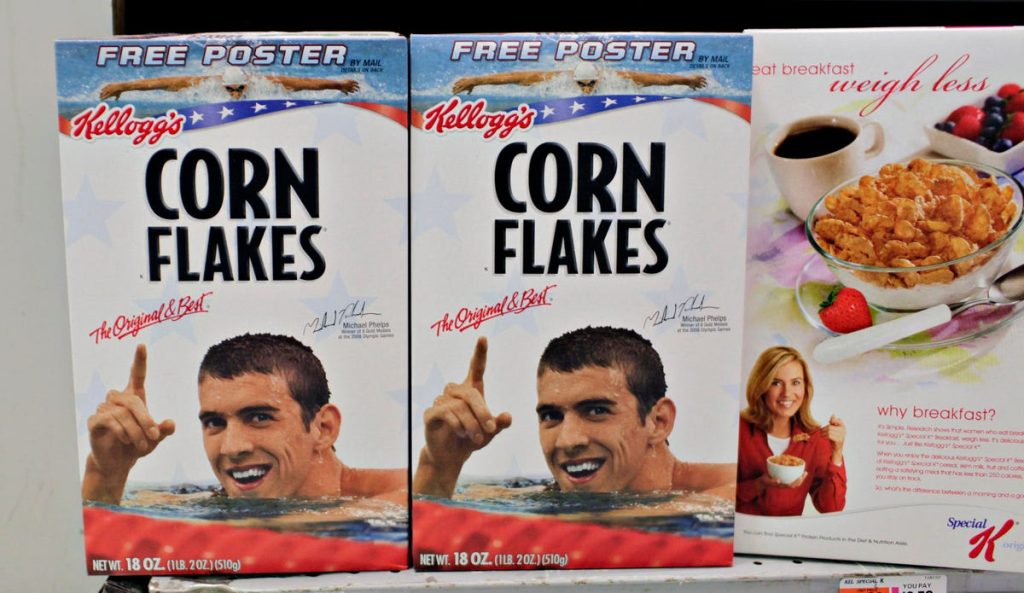

What caught my eye, however, was the fact that Bankman-Fried used celebrity endorsements of his schemes. This is surely a strange and not entirely reassuring phenomenon. For example, an American footballer called Tom Brady and his former wife, a model, Giselle Bündchen (of neither of whom had I previously heard) were used, and paid, to endorse his business. Other celebrities were similarly employed.

I presume that evidence exists that such advertising by celebrities actually works; it’s when you think about why it should work that your heart begins to sink. After all, asking an American footballer for his advice on blockchain investments is probably as sensible as asking the local barfly who has propped up a bar for the past 25 years for his opinion on the latest advances in cardiac surgery. It’s true that experts aren’t always right, but specialist knowledge and experience still count for quite a lot, for all the inevitable incompleteness of human understanding.

The idea of sympathetic magic illuminates the phenomenon of celebrity endorsement of products of whose virtues or defects the celebrities can have no special knowledge. Sympathetic magic is the use of an object associated with someone either to influence him or to become in some desired respect like him. It can go as far as cannibalism: eating part of someone in order to add his to one’s own potency, for example. I need hardly add that this is all very primitive and, you might have thought, out of place in a society as dependent as ours on sophisticated technology. But the primitive is like the magma under the surface of the Earth; it keeps breaking through however unwanted or destructive it may be.

In England, for example, grossly fat and out-of-condition men, whose idea of physical exertion is fighting their way to the bar, don the football shirts of their favorite team, as if by doing so they were partaking in some small way of the skill and prowess of the players, without having to go through the arduous training necessary really to do so (to say nothing of the age difference between them).

Likewise, when a celebrity advertises or “endorses” a product, the natural though not necessarily true assumption being that he uses it himself, the purchaser imagines that he’s sharing something with that celebrity, becoming in some intangible and desired respect a little more like him.

This is no great tribute to the rationality of the so-called rational animal, man. Nor should we comfort ourselves that it’s only the less intelligent or educated portion of humanity that is affected in this way. The endorsements of Bankman-Fried’s companies were not directed at those at the lowest level of society, rather the reverse. Even well-educated people, then (at least if such advertisements work), are susceptible to the lure and cult of celebrity.

The type of celebrity used in such advertisements tells us quite a lot about the scale of values prevalent in any society. Some time ago, while writing a book about three murders committed in the 1840s on the small island of Jersey in the English Channel, I discovered that about half the advertising revenue of local newspapers of that period depended on advertisements for proprietary remedies (and half of them either allegedly preventive or curative of syphilis); many of these remedies were sold as a side-line by the editors or owners of the newspapers, a fine example of economic synergy. And many of the advertisements carried endorsements, not by sports stars, who then hardly existed, but by aristocrats. If Lady X or Lord Y vouched for a product, you raised your social standing, at least in your dreams, if you too used it. Thus, joining the aristocracy was the dream of many people.

I’m not sure that there’s no new thing under the sun, but there’s no entirely new thing under the sun, and the magical thinking encouraged by celebrity endorsement isn’t without precedent.

When it comes to investment advice, I certainly wouldn’t take it from a sports star, but it doesn’t follow from the fact that I know from whom I shouldn’t take it that I know from whom I should do so. That, of course, is a much deeper problem, as I have found recently.

First published in the Epoch Times.