The Two Roads: Referendum or Representative Democracy

by Michael Curtis

Winston Churchill said it in the House of Commons on November 11, 1947, “No one pretends that democracy is perfect or all-wise. Indeed, it has been said that democracy is the worst form of government except for all those other forms.” He had earlier remarked, in the House, on December 8, 1944 that the foundation of democracy was the citizen “putting his cross on the ballot paper in strict secrecy.” He did not deal with the difference between that cross being exercised by direct democracy, the opportunity to vote directly on policy issues, or by representative government. Europe has recently dealt with and still faces the dilemma of the two political roads that diverged but were both taken on this issue.

The experience of representative government was shown in the European Parliament election in May 2019 which had a mixed result. It showed the survival but decline in popularity of the traditional mainstream center right and center left parties, and the increase in support for Far Right and Green parties. The result is a more fragmented European parliament, the need for a broader coalition for decisions to be reached, and political uncertainty and instability in deciding on senior positions, leadership in the European Commission, European Central Bank, and European Council, in the EU, and future battles over significant issues, the eurozone, migration, climate change, relations with the U.S. and Russia, and Brexit.

It is the Brexit issue, based on referendum, that has led to the present expression of the increasing polarization of European opinion. Now that the new political party, led by Nigel Farage a new party only two months old, obtained 31% of the vote in the EP election, it is an issue that calls not only for likelihood of changes in the British political world, but also a reexamination of a neglected issue of the electoral system, the method by which the will of the people is expressed.

It may be too strong to say that the metaphor of mighty oaks from little acorns grow is a precise image of British politics today, but the success of Brexit is a commentary on the danger of direct voting by the population on political issues. The advocates of Brexit, the simple question of membership of the EU, have pushed all other issues into the background, but offered no solution how to escape the consequences of how its objective is to be achieved.

At the core of the problem is the method by which the “will of the people” is to be expressed in democratic systems. On December 10, 1948 the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights which stated, Article 21, that “the will of the people shall be the basis of the authority of government.” This will shall be expressed in periodic and genuine elections…which shall be held by secret vote or by equivalent free voting procedures. The Declaration can be regarded as the milestone document in the history of human rights in suggesting a common standard for all peoples and nations. But it left open both the nature of the genuine elections and how they should be conducted, and the reality of a social contract by which individuals consent to submit to authority in exchange for protection and the maintenance of a social order.

An acceptable working definition is that democracy in a country is sustained by consent of the people, and that legitimacy of rule is based on consent. The fundamental question is whether the people make or approve the rules directly or through some form of representation.

Direct action is a referendum or plebiscite, binding or advisory, that occurs when the whole electorate of a particular political unit, country or region, votes on a specific proposal of legislation, or initiative. It can be binding or advisory. It is an expression of direct democracy, in contrast to representative democracy. It has been most often used in Switzerland, which has had 600 votes since 1848. In the U.S. the device has not been used in a national referendum, but has been used most frequently in California with votes on taxes and budget. This in itself can be seen as failure of the political system since referenda are often used because politicians could not agree on the issue.

The case for direct democracy was forcefully made by Jean-Jacques Rousseau who held that “the will” cannot be represented: “Were there a people of gods, their government would be democratic. So perfect a government is not for men.” But the idea of a will based on referendum instead of representation by elected officials is troublesome for a number of reasons. Even Rousseau conceded that direct democracy, a plebiscite, is not feasible beyond a small territorial area and a small number of people. A second problem is that a vote may be the outcome of momentary of genuine or manufactured crisis enthusiasm rather than on genuine and serious reflection. Third, a direct vote may , and has led to an undemocratic conclusion; witnesses are the votes for Benito Mussolini, yes or no on a list of deputies nominated by the Grand Council of Fascism, in 1934, for Adolf Hitler, military occupation of the Rhineland, in 1936, and Ferdinand Marcos 1973, who used referenda to ratify the 1975 constitution and approve actions such as the closing of Congress.

The danger of majority rule was pointed out by James Madison who was concerned for protection of the rights of minorities, while acknowledging that the majority of representatives in a body had the right to speak for the whole. In his letter of October 24, 1787 to Thomas Jefferson he expressed concern that a majority, united by a common interest or a passion may oppress the minority. The tyranny of the majority, therefore, could only be prevented by a system of checks and balances, or by revolution as the ultimate remedy in extreme cases of government tyranny.

Britain is a country of representative democracy, on the principle of Parliamentary sovereignty, but it has had referenda in 1975, 2011, and 2016, all on single issues. In 1975 the country voted on the non-binding proposal, “Do you think the UK should stay in the European Community (Common Market)?” In a turnout of 64% the result was affirmative, 67.23% to 32.7%. In 2011 a vote in a turnout of 42% was on “Should the “alternative vote” system be used instead of the present first past the post system?” The only UK national referendum on a domestic issue, it was defeated, 32.1% no to 67.9% yes.

The present political issue stems from a pledge made in January 2013 and again in November 26, 2013 in an article in The Financial Times by the then Conservative Prime Minister David Cameron, under pressure from some of his Conservative party members and by the Ukip, that he would call a referendum on the EU. If the Tories won the general election he would renegotiate the UK relationship with the EU and then give the people the simple choice between Remaining or Leaving.

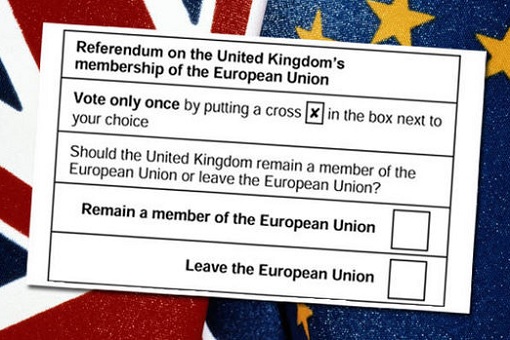

The referendum that has come to be called Brexit took place on June 23, 2016 on the simple question, “Should UK Remain or Leave the EU.” In a 72% turnout, the vote was for leaving, 51.9% to 48.11%. Though it was non-binding, the government promised to implement the result. PM David Cameron, who had initiated the referendum and campaigned for Remain, resigned as a result of the loss.

The young in the electorate tended to support Remain. There was no apparent gender split. Regions differed, Greater London, 69-40, and Scotland, 62-38, were strongly for Remain. Wales was for Leave. However, the vote was on a simple issue of membership of EU, not on terms of exit, nor on future relations with EU countries after leaving. The following two years have been painful for UK, and for the EU too, with the countless differences over the economic effects of Leave, in terms of jobs that might be lost or gained, or trade, of taxes, or immigration, and its effect on public services, schools and hospitals.

Because of the strong feeling on the issue, in a sense the referendum in Britain can be said to have been more about immigration, than about the EU. All, in the U.S. as well as in Europe, recognize that immigration is a thorny issue which has no easy solution. It is not an issue for a referendum but one that must be resolved by representative democracy.