by Lev Tsitrin

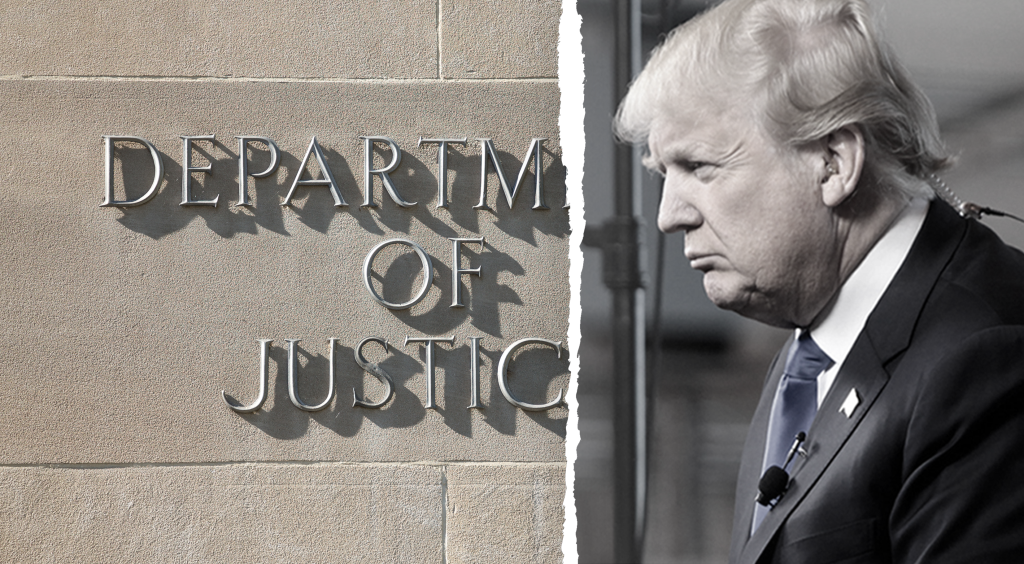

“Trump’s modus operandi is to undermine any institution that stands up to him, whether the news media or the military or the courts. Causing people to lose confidence in the judiciary may be precisely what Trump is banking on,” Peter Coy of the New York Times suggests in his column titled “This Is Why Trump Keeps Antagonizing the Judge in His Fraud Trial.” To bring the point home, the visual preceding the column shows Trump as a steamroller driver, about to knock to the ground the common symbol of impartial judging — the two-tray balance on which parties’ argument gets weighted by a judge.

Mr. Coy’s factual basis for this grand assertion hardly measures up to it though — in his New York State trial over valuation of his real estate holdings, Trump’s lawyers keep reintroducing the argument which the judge already rejected, and Mr. Coy himself provided a much simpler, and more cogent explanation: lawyers are just “making sure that trial records include all arguments that they might want to put forth on appeal. It’s a basic principle of litigation that any argument that isn’t raised at trial cannot be raised on appeal.”

I don’t want to be nitpicky, and won’t take Mr. Coy to task for refusing to use Occam’s razor — the principle that the simplest adequate explanation should suffice. I understand that in the noble task of bashing Trump the nobility of the task trumps the notion of intellectual integrity — so let me get to the larger point left unmentioned by Mr. Coy: should judges (and I am talking about federal judges here) — be trusted? Shouldn’t the dictum of “trust, but verify” apply to federal judges, too?

By now, I know that the mainstream press responds to this question, when I pose it to the journalists, with a resounding “no.” Absolute, unthinking trust in the integrity of the federal judiciary is an article of our civic faith; it is as unthinkable to doubt it, as it was unthinkable to doubt the awesome goodness of His Majesty George III way back when — in the colonial America before the Stamp Act. Some things in our civic religion must stay unapproachably holy; to peek into them is sacrilege.

And yet, as we all know (or at least, should know), “power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” Due to public subservience that manifests itself in the total absence of even a thought of critical public scrutiny of how federal judges operate, those judges have become so arrogant of their power, and so corrupt, that they don’t even mind openly stating that they are corrupt: in Pierson v Ray judges gave themselves the right to act from the bench “maliciously and corruptly,” no less. I wish Mr. Coy would dedicate a column to this fascinating fact — but having e-mailed the New York Times perhaps a hundred times, and having picketed its building with a large sign — all to no avail, I do not hold my breath. Mainstream journalism is monumentally dishonest and self-serving; Mr. Coy apparently sees as totally normal the situation where to speak up against the judge is — to quote a passage from his column — to “tug on Superman’s cape, […to] spit into the wind,”

Why do we see judges as superhuman, as akin to the elements that cannot be reasoned with — and brought to reason? Why did we set them up on this pedestal, and why do journalists refuse to examine how federal judges decide cases, and show — for all to see — the clay feet of those we imagine to be some giants of legal thought? I can tell you, Mr. Coy, that no great Olympian wisdom goes into making a decision; simple swindle of replacing parties’ argument in the trays of the scale of Justice with the bogus argument of judges’ own concoction that allows for the decision the judge wants to make, suffices. This, of course, is a brazen violation of “due process” presumably guaranteed us by the Constitution — but no one cares to notice; the likes of the New York Times, and of its columnists, are happy not to see this elegant sleight-of-hand that allows federal judges to decide cases anyway they want, facts and law be damned. Trump is all that journalists want to talk about. Federal judges are above all scrutiny, are above all criticism, are above all journalistic investigations. Nominally a republic, we enthroned judges to be our God-given kings.

Well, His Majesty George III was likewise venerated — until he wasn’t; nor should we venerate federal judges. If President Trump helps the public make a mental adjustment that is needed to treat federal judges not as gods but as government — and thus subject to public scrutiny and public criticism like the other two branches of government which our press does investigate — he will make a tremendous contribution to America. Mr. Coy (and the illustrator at the New York Times) are, in this particular instance, overstating Mr. Trump’s intentions, I’m afraid. But I wish Mr. Trump could indeed open the public’s eyes to the massive, systemic swindling that is happening on the “corrupt and malicious” federal benches, and force the likes of the New York Times — and of Mr. Coy — to finally confront the issue of judicial fraud that we refuse to see though it stares us right in the eye.

Lev Tsitrin is the author of “Why Do Judges Act as Lawyers?: A Guide to What’s Wrong with American Law“

6 Responses

Trump convicted by a judge of fraud in a case where no one was defrauded. All of the bank loans were repaid and no bank complained. What more evidence does anyone need to know that the system is corrupt. The DA who brought the indictment is no better.

Does not judicial review via the appeal process provide protection against lower court wrong decisions? At the Supreme Court level cannot decisions be reversed, though at great cost in time and legal fees?

Is there not a federal jury system for Trump-type cases to oppose or nullify a judge’s malfeasance?

Excellent questions all, and the answers are unfortunately “no”. The problem is that “wrong decisions” are a result of a deliberate violation of judicial procedure that is purposefully aimed at attaining that, “wrong” result. In a sense, the decision is not “wrong” but fraudulent — and there is absolutely no guarantee that the appellate court won’t resort to the same fraudulent procedure And the Supreme Court is no different in that respect — the only difference being that it acts as a single judge, and has no physical capacity to hear cases, thus rejecting some 98% of petitions. As to jury trials — juries only decide on the factual aspect of a case; judge still decides on the law. So juries are not an all-powerful override on judges, either…

You couldn’t have a better poster boy for your argument against judicial tyranny than the current presiding judge of Trump, Justice Arthur Engoron – who has blatantly said that he bases his decisions on his emotions and would overrule the jury if his feelings so dictated.

Engoron’s stated position gives grounds for forced recusal or mistrial for his threat to, in effect. reject the law.

How does the judge’s Oath of Office read?!

Is the judge allowed to be a mob of one?

Arguments in that form are fraudulent insofar as they tend to knowingly and falsely create the presumption they purport to defend, in this case that someone trusts the US judiciary.

Who on earth can possibly be left who does that?

If I were to be caught in the US for any offense, not actually committed by me, I assume I would be railroaded as a matter of course, whether by cop pressure to talk, DA pressure to take a deal, or judges biased however they are biased.

I doubt anyone from outside the US doesn’t think the US judiciary or more widely US law enforcement is corrupt. Only the exact reasons change from one person to the next.

I just assume Americans think the same.