We concluded that practically all of western Canada, and the sizeable conservative minority in eastern Canada, were practically unrepresented in the national media

by Conrad Black

The reasons my associates at the time and I founded the National Post 20 years ago were a combination of commercial and public-spirited motives. By then, we had bought the Southam, Sifton, Unimedia and many of the smaller Thomson newspapers, and owned 58 of the 105 daily newspapers in Canada. These holdings included all the daily newspapers in Newfoundland, Prince Edward Island, and Saskatchewan, and both daily newspapers in Vancouver, the principal daily newspapers in Calgary, Edmonton, Quebec City, Windsor, Victoria, the daily English language newspaper in Montreal, the leading English newspaper in Ottawa as well as the French newspaper in that city, and the second newspaper in Halifax.

This position naturally led to a widespread imputation to us, and to me personally, of trying to mould public opinion in Canada and push and bully office-holders into policies we favoured, or that could be of particular material benefit to us. That was not, in fact, how we managed our business, but as I discovered in other spheres, public perceptions as created by the media, and facts are frequently completely disconnected. My late, distinguished senior partner, John A. McDougald, used to say that critics, especially media critics, mistakenly assume that people in positions of some wealth or influence behave as they themselves would in those positions.

Our practice was to invest in product quality, and build circulation and advertising on the back of that. We transferred to the principal Canadian titles the policies we had implemented in the resurrection of the London Daily Telegraph from insolvency. It had an aging readership and was a newspaper that carried only news and sports, and little finance, features, or interesting comment. We turned it into the most respected and profitable general newspaper in Europe with a daily circulation exceeding one million and an enviable demographic.

Readers in Ottawa, Calgary, Edmonton, and Vancouver, in particular, will, I think, recall the sharp improvement in the quality of the principal newspapers in those cities, starting in 1996. The late Neil Reynolds as editor, and Russell Mills as publisher, carried out their mandate from us to transform the Ottawa Citizen into a “newspaper worthy of the capital of a G-7 country.” They made it a newspaper for all of us, and all Ottawans, to be proud of, and its circulation, advertising revenue and profit rose.

The old Southam management had developed the practice of complete non-interference in the editorial process, with the general result that the editors were simply chairpersons of the editorial department and everyone did pretty much as they wished, with the observation of reasonable guidelines against defamation. The result was that initiative lagged, and comment and reporting became generally blurred and the soft-left biases of most members of what was rather self-flatteringly called the working press permeated the content of the newspapers, and alienated the local business communities that provided the advertising revenues, and also disappointed the discerning readers who knew the differences between a crisp, well-written product, and the almost unedited self-indulgence of indolent leftist journalists. It was approximately parallel to the difference between a place of education and a daycare centre.

We went over budgets with publishers, and agreed on reasonable efficiencies in the non-editorial areas. In the editorial departments, we asked for more enterprise and better writing and the absolute enforcement of the distinction between reporting and comment. Reporters who wanted to write signed comment pieces were welcome to do it, but not in the guise of objective reporting. In Britain, the leader of the Labour Party, Neil Kinnock, told me a number of times that he read the Daily Telegraph first because it was the fairest and most perceptive in its parliamentary coverage, even though in editorial matters we were an unwavering and stentorian supporter of the three-term Conservative prime minister, Margaret Thatcher. In the process, we sponsored a rescue plan for the Canadian Press, because my then-associate David Radler and I believed that Canada had to have a co-operative press association. We also made available the contents of the Telegraph newspapers, the London Spectator, Jerusalem Post, and the Chicago Sun-Times, all of which we also owned, and imported their relevant content to the Canadian titles as the local editors might wish. Thus did Mark Steyn, in particular, make his debut in his native country.

These techniques worked generally and the profits of the Southam chain almost tripled in three years. But even as we were accused of seeking to exercise a Mephistophelean influence in this country, we had in fact, almost no influence on national affairs. Canadian public policy was almost exclusively aligned with the soft-left consensus endlessly imparted by the Globe and Mail and Toronto Star and the French and English CBC, with the occasional contribution of Maclean’s trotting along beside them. Canada was essentially governed always somewhat to the left of the United States and took a corresponding position in international affairs, and conceded practically anything short of outright independence to the Quebec nationalists. That had been the unchanging line since The Globe and Mail ceased to be a conservative-leaning newspaper in about 1980. There were no other appreciable pressures on federal affairs other than from farther left, especially from the NDP and its activists in organized labour and the academic and media communities.

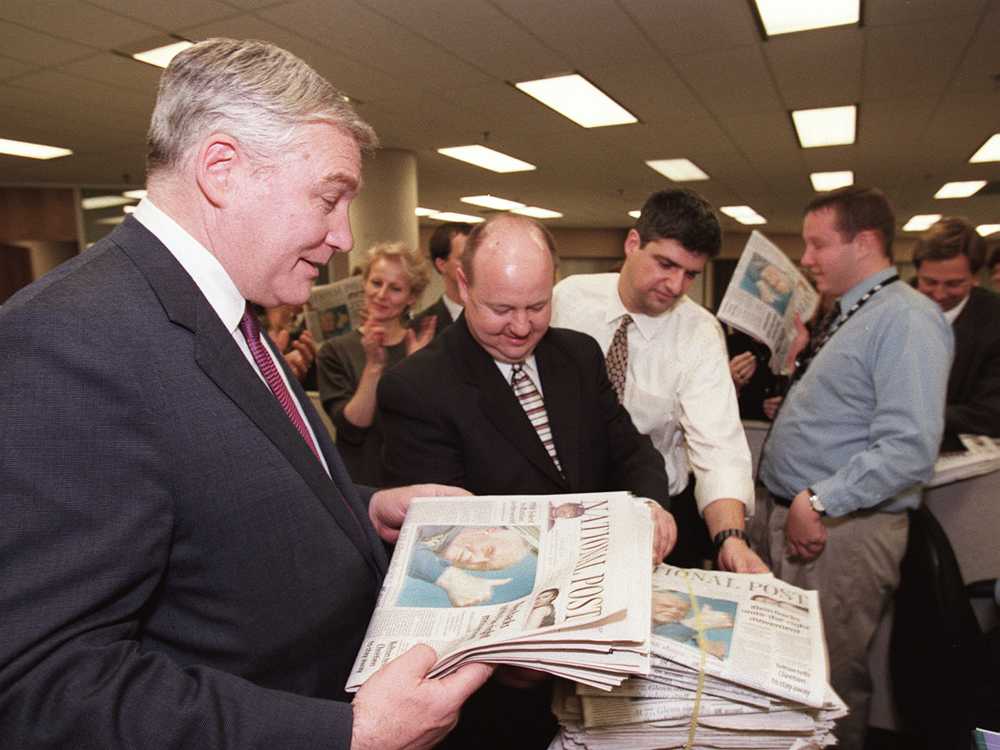

My associates and I concluded that practically all of western Canada, and the sizeable conservative (whether traditionalist or libertarian) minority in eastern Canada, were practically unrepresented in the national media. Coincidentally, our company, although it owned most of the daily newspapers in Canada, was not represented in its largest city, Toronto. We were pilloried for trying to exercise undue influence on federal affairs, when we in fact had no influence at all (and in any case were not trying to exercise any). There was also a discernible discount to our stock price due to our absence from Canada’s principal market. The solution to these gaps was obvious. We began by buying the Financial Post, which I had co-founded as a daily newspaper with the publisher of the Sun, Doug Creighton, and with the Financial Times of the U.K. in the early Eighties. After a careful canvass, Ken Whyte, the editor of Saturday Night, which we also owned, was recruited by me as editor of the new national newspaper, whose name was suggested by our distinguished colleague on our board of directors, Gen. Richard Rohmer.

The Globe and Mail was more vulnerable than it appeared; it was the third newspaper in Toronto circulation, and its status as a national newspaper was due to a few add-on bits in local editions across the country, in cities where, except for Winnipeg, we had the principal local newspaper. Ken did an astonishingly effective, if costly, job of recruiting. And although it was understood that he would not poach anyone from our British titles unless there was a distinct Canadian connection, he developed what my wife Barbara Amiel, former editor of the Toronto Sun and our editorial vice president, called “The Ken Whyte broad-jump.” If a Daily Telegraph journalist’s grandmother had gone to a summer camp in Quebec before the First World War, he held that the journalist was eligible for poaching.

As readers will recall, Ken built a splendid newspaper, and it distinctly changed and broadened political coverage and opinion throughout the country. It also worked commercially. Though competing newspaper companies claimed we squandered mountains of money on the start-up, it was within budget and the subsequent sale of the business to CanWest, after I became concerned about the commercial future of newspapers generally, fully justified the investment.

Besides that, apart from the very greatest days in Fleet Street, it was the most fun most of us ever had in newspapers. For all of us who had a hand in it, the National Post was and will always remain a subject of pride.

First published in the National Post.

- Like

- Digg

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link