Will Vladimir Putin Score Again?

by Michael Curtis

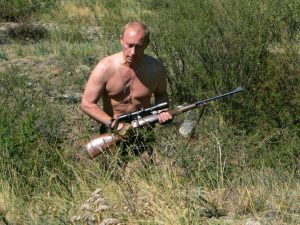

We have seen the body if not the soul of Vladimir Putin, fit and vigorous, eminent sportsman, black belt holder in judo, who was the young judo champion in St. Petersburg, competitor for Formula One automobile competition where he reached speed of 150 m.p.h., pilot of fighter jets, and rider of Harley Davidson motorcycles. He is also an ice hockey champion, always the highest scorer in a team that never loses.

On his 63rd birthday in 2015 Putin played in an ice hockey game in Sochi. His team won 15-10 with Putin, who wore a uniform of colors of the Russian flag, scoring seven goals. In an exhibition game in May 2019 in Sochi, Putin’s team won 14-7 and he scored eight goals before he fell flat on his face. In another game on December 29, 2021 in St. Petersburg, Putin teamed up with the Belarus president Alexander Lukashenko. Putin scored seven goals while Lukashenko scored two in a victory 18-7 of their team. Noticeably, the rival team seemed reluctant to resist Putin as he skated towards the goal.

Putin is good with a Puck but he is not Robin Goodfellow. His hockey success and thrashing of opponents raises two questions relevant to the arena of political and military affairs. One, is Putin skating on thin ice and is his relish for ice hockey a symbol of his version of the Cold War? The second is whether other nations, the U.S. and NATO, will be as reluctant as his hockey opponents to resist his acts.

First is the puzzle of Russia’s intentions regarding Ukraine, a former Soviet Republic with social and cultural ties to it and eight million ethnic Russians. Spokespeople for Russia declare it has no plans to invade the country, but what then are the reasons for the massing of troops and weaponry close to its border? As a minimum, the given explanation is that Ukraine must never join NATO. More aggressively, Ukraine is seen as linked to, or as a part of Russia, not as a separate country.

Even more generally, Russian policy touches on at least four factors: to restore its influence in Eastern Europe; to end the eastward expansion of NATO now that 12 countries, from Estonia to Bulgaria, have joined since 1997; to prevent any NATO activity in Eastern Europe; and to eliminate NATO combat units in Poland, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. Putin calls for NATO to pull back from pre 1997 lines in accordance with the agreement between President Bill Clinton and Boris Yeltsin that former Soviet states and Warsaw bloc nations could choose whether to apply to NATO for membership.

Basic to understanding his policy is that Putin wants to stay in power. He was lucky he gained power at a moment when Russia was benefiting from foreign investment: rising oil, gas, and mineral prices, and relative political stability. His position is more precarious now in a period of lower energy prices and problems of growth, and Putin portrays himself as defender of a besieged motherland, against supposed threats from Finland in the north to Georgia in the south. He also sees the process, under the presidency of Alexander Zelensky, of increasing Ukrainization in the country and the reduction in the teaching of the Russian language in the schools.

Signs of Putin’s aggressive are manifest. He wants to recreate a Russian empire, one akin to the power of the Soviet Union. Russia has stationed 100,000 troops close to the border with Ukraine accompanied with tanks, heavy artillery, reconnaissance, field hospitals. It is moving S-400 surface to air missile systems into Belarus and has moved ships near shores of Ukraine.

Putin reasserted influence over the Caucasus after the 2008 war by occupying 20 per cent of its territory. He helped keep his ice hockey partner Belarusian President Lukashenko, who has threatened to cut supplies of gas to Europe and has caused a migrant crisis, in power. Putin intervened in Kazakhstan with a squad of paratroopers to save President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev and helped him in a struggle with his predecessor and rival, to declare a state of emergency, shoot troublemakers and crush the revolt. He is helping Serb leader Milorad Dodi in Bosnia- Herzegovina and planning to send Russian gas to the region via the Black Sea. Putin will deploy troops to Mali after French move out of Timbuktu.

Illustrating its strength, Russia fired Zircon hypersonic cruise missiles on December 24,2021, missiles that can carry both nuclear and conventional warheads.

How to deal with Moscow? Diplomatic activity so far has failed to ease tensions, though maintaining the dialogue with Moscow remains the first priority. Western authorities hold that the international community should not tolerate any action which undermines Ukrainian sovereignty. Yet they have issued mixed messages of “grave or massive consequences” if Russia invades. There is no policy of appeasement but the response of NATO countries has varied and remains unclear, while the Unites States has no firm definite position.

Britain has sent military hardware to Kiev, planes, 2,000 short range anti-tank missiles.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson has said that the UK would contribute to any new NATO deployment. It has already supplied Ukraine with thousands of anti-tank weapons. He declared that the British army leads the battle group in Estonia and will protect allies in Europe.

Denmark is sending a frigate to the Baltic Sea and plans to deploy four F-16 fighter jets to Lithuania. The Netherlands is sending two F-35 fighter planes to Bulgaria. Spain is sending ships and may send fighter jets to Bulgaria.

France has said it could send troops to Romania. However, President Emmanuel Macron has advocated what appears to be a separate European security and stability strategic partnership between Russia and the EU, separate from NATO: “ I haven’t “, he said, “detected anything concrete coming out of the talks with the U.S.” The European Commission has said it will not withdraw its embassy staff from Kiev, yet the EU has plans for loans and grants to Kiev though this will need approval from member states.

The surprise is the ambivalence of Germany, either for what it conceives as its self-interest or a genuine belief on intercedence with Russia. The new German Chancellor Olaf Scholz issued a vague threat that grave consequences would follow if Moscow invaded Ukraine. One may ask what “kind of consequences.” Scholz has said there are ways other than military ones, “to achieve de-escalation.” Russia is investing in the German economy, and Germany is not imposing an embargo of Russian exports and strategic minerals.

It is understandable that Germany is reliant on Russian gas, especially in winter, and gives mixes signals over the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline but its policy is not appreciated by fellow EU members. So far Berlin has refused to allow arms exports to Ukraine because of its policy of not sending weapons to conflict zones. It is blocking Estonia from sending howitzers to Ukraine, because the weapons originated in Germany.

The U.S. has ordered 8,500 troops to be on standby for deployment but the Pentagon has stated that U.S. deployment would be part of a NATO response force. Biden, like Donald Trump, has held that the $11 billion Russian owned pipeline, Nord Stream 2, will not be allowed to operate in Ukraine is invaded. Biden declared he will impose mandatory sanctions if Moscow increases hostilities or invades Ukraine.

But Biden’s ill-considered words about a probable minor U.S. response to Russian minor incursions, whatever that entails, and his argument that a “mere minor incursion” might divide the West, show a confused mind or indecisive policy, or at best strategic ambiguity.

The vital question is whether the U.S. and the West is genuinely serious about preventing or countering Russian aggression. The fact that Ukraine is nor a member of NATO should not prevent Western deployment. Certainly, the West cannot become allow Putin the right to veto NATO membership.

The opponents of Putin do not make a team, in international affairs as in hockey, but they should agree on possible actions. But they are not a paper tiger. A number of suggestions might be considered. Preventing the opening of Nord Stream 2 pipeline if Russia is belligerent. Aid should be given to Ukraine for its self-defense, anti-tank and anti-aircraft missiles, maritime security and intelligence. In every way raise the costs of a Russian invasion. Deny access to the Swift financial system for dollar transactions. Impose export controls on important sectors of the Russian economy, including an export ban of microelectronics. Pull diplomatic staff out of Kiev if it continues to be threatened.

In the U.S. the decision to act against the possible aggression of Putin forces should not be handicapped by political party divisions. The U.S. should counter Pupin’s demand that NATO remove its forces from its eastern members.

Above all, the U.S. and the West should remember the fallacy of appeasement policy and of the foolish words of Neville Chamberlain in 1938 that resistance to Nazi Germany would mean involvement in “a quarrel io a far-away land between people of which we know nothing.”