Working With the Gipper

By Bruce Bawer

Frank Lavin was appointed by George W. Bush as Ambassador to Singapore and, later, as Under Secretary of Commerce for International Trade. Until recently, he was CEO of Export Now, which is described by Wikipedia as “a company dedicated to helping consumer brands sell their products in China.” At present, he’s a Visiting Fellow at the Hoover Institution. But long before holding down these positions, Lavin worked in the Reagan White House, an experience that he recounts engagingly in his brief but anecdote-rich new book Inside the Reagan White House: A Front-Row Seat to Presidential Leadership with Lessons for Today.

The book’s structure is partly chronological, following Lavin from one White House job to the next, and partly thematic, with chapters on Nancy Reagan as First Lady (Lavin is less critical of her than some Reagan observers have been) and on Ronald Reagan as the “Great Communicator.” Lavin wants to capture the day-to-day atmosphere of the West Wing as well as to convey the goals of the Reagan presidency; he succeeds nicely on all counts.

The book’s structure is partly chronological, following Lavin from one White House job to the next, and partly thematic, with chapters on Nancy Reagan as First Lady (Lavin is less critical of her than some Reagan observers have been) and on Ronald Reagan as the “Great Communicator.” Lavin wants to capture the day-to-day atmosphere of the West Wing as well as to convey the goals of the Reagan presidency; he succeeds nicely on all counts.

Born in Ohio, Lavin attended Andover, earned degrees in Foreign Service and Chinese from Georgetown, and studied International Relations at Johns Hookins and Finance at Wharton. His White House career started in 1983, when he was named associate director of the Office of Public Liaison (OPL), which was “responsible for constituency outreach.” In 1985-86 he was at the National Security Council; and from 1987 to 1989 he served as director of the Office of Political Affairs. A major part of his job was to deal with people who had come to visit the president; hence he spent a good deal more time with Reagan than many other staffers did.

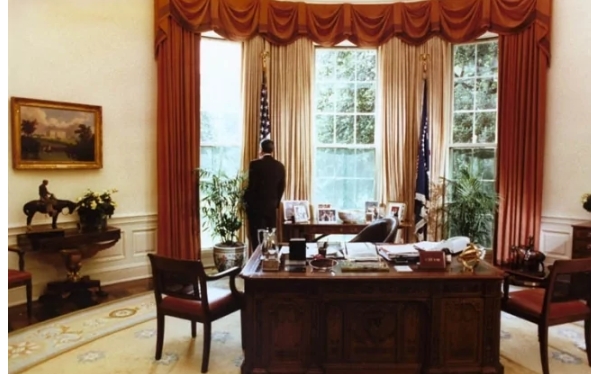

And his verdict on the man is unqualified: “Up close it was a delight to work with Reagan….When he received visitors in the Oval Office, he radiated bonhomie.” Lavin even goes so far as to say that “the two nicest people in the West Wing were Ronald Reagan and George Bush. If you were in a hurry and bumped into one of them rounding a corner, despite your horror, it would be Reagan or Bush who would apologize to you.”

Lavin offers several anecdotes that illustrate Reagan’s sensitivity. When a group of disabled children visited the Oval Office and asked the president questions, one of them “had a severe speech impediment” that made his question impossible for anyone to make out. “The president asked him if he could repeat it and again no one could understand what was said. The staff froze. The teachers froze. What was to have been an upbeat day was potentially a disaster. Instead of allowing these wonderful kids to forget about their disabilities, this kid was going to be reminded of it. Reagan was quick to come to the rescue: ‘I’m sorry,’ he said with a smile, ‘but you know I’ve got this hearing aid in my ear. Every once in a while the darn thing just conks out on me. And it’s just gone dead.’”

Lavin recalls another touching episode. When he and his wife lost their unborn child shortly before the due date, they were devastated. Then Lavin’s office phone rang. “The boss,” he was told, wanted to see him. Lavin went up to the Oval Office to find a president who “somehow seemed a bit more somber than usual.” Reagan said, “I heard about what happened….The same thing happened to us once. It’s a terrible thing.” As Lavin later learned, Reagan had indeed lost an unborn child – not with Nancy, however, but with his first wife, the actress Jane Wyman, about whom he was famously tight-lipped during his years with Nancy (reducing their nine-year marriage, in his 1990 autobiography, to a couple of sentences).

That’s not the only interesting Wyman-related anecdote in Lavin’s book. Once, when Lavin was in his office outside of ordinary working hours, he turned on the TV to see the news, which was usually available for playback over the White House’s TV system, but instead saw Wyman’s CBS series Falcon Crest (back in those ancient times, it was apparently impossible during off-hours to dial into two different shows on playback on White House TV sets); when Lavin phoned the communications office to ask about it, he learned that the TV news was unavailable because somebody in the family quarters – either Ron or Nancy, or both – was watching Wyman’s show.

There were amusing moments. During a 1982 state visit to Britain, Reagan went horse riding with Queen Elizabeth. When the queen’s horse broke wind rather loudly, she apologized, to which he replied: “That’s OK, ma’am. If you hadn’t said anything, I would have thought it was the horse.” And speaking of Britain, Lavin admits to being nothing less than shocked when he first observed the familiarity with which Margaret Thatcher treated Reagan. “‘Now, Ronnie, here’s what you need to do…’ she said at one point. I wheeled to look at him, expecting a glower, but he was taking it all in. If you are the president of the United States, there are basically no peer relationships.” But the Iron Lady was the exception. “Thatcher was perhaps the only leader in the world who shared the president’s philosophy, spoke native English, and had the self-confidence to assert herself.”

Then there’s this. We think of Reagan as a man who kept his language clean, but when asked if Soviet General Secretary Yuri Andropov died, Reagan instantly rejected the suggestion that he attend the man’s funeral: “I don’t want to honor that prick.”

Like other insiders, Lavin fiercely dismisses the notion, long spread by his opponents, that Reagan was a buffoon, or at the very least detached from his job and his surroundings. But it is true, apparently, that for all his chronic geniality with underlings, he “made little effort to learn staff names, even for people he worked with daily. It was said that [Richard] Darman delivered papers to the Oval Office and spoke with Reagan daily, but even after a year, Reagan did not know his name.” Nor, maintains Lavin, was the Gipper the most introspective of men; on the contrary, he “cultivated an absence of introspection with an almost Zen-like perfection of obliviousness. He brought confidence, optimism, but little ego into the discussion.”

Nonetheless, his knowledge of particulars, and his ability to express them fluently in writing, could be formidable. Not long after returning from the Reykjavik summit, Reagan was handed a draft of the speech, written by the arms control staff, that the president was to give on TV that evening. It turned out that Reagan had written his own draft in longhand – and that his draft was “significantly sharper and clearer” than the text prepared by the arms experts.

It’s true that his busy schedule in the White House made it difficult for Reagan to write his own speeches; but anybody who has read the collection of radio commentaries and other addresses that he did write before his presidency knows that he could do so expertly and with ease.

Lavin’s book represents a welcome addition to the Reagan shelf. Unfortunately he finds it necessary to contrast Reagan with Trump, whom he patently despises. In fact, Lavin asserts that it was the events of January 6, 2021, that persuaded him to write this volume. The so-called insurrection, he laments, violated the tenets by which Reagan governed, and so did the first term of Trump.

Among those tenets: “Tone matters. Be careful of personal conduct…using communication to demean others makes it harder for some to support you.” Perhaps, but I would submit that Trump’s use of snappy monikers like “Low-Energy Jeb” helped clear the GOP pack and save America from yet another middling Bush presidency.

Another rule: “Inclusivity matters…The Republican Party was founded on a set of ideas rather than a group identity, so people from any background should be welcome.” Sorry, but, Reagan’s own personal tolerance notwithstanding, the idea that the pre-Trump GOP was a big tent is preposterous; not until Trump came along, for example, did gratuitous gay-bashing cease to be a standard feature of Republican campaign rhetoric.

In his comparison of Reagan to Trump, Lavin speaks up for the value of “international leadership,” praising Reagan for having “set the stage” for NAFTA and faulting Trump for his public criticism of “our NATO allies.” Nonsense: NAFTA severely damaged the manufacturing base in the Rust Belt, which Trump is restoring to economic health; as for Trump and NATO, he pressured allies to kick in to the NATO budget, thus strengthening the alliance.

Finally, Lavin faults Trump for his personality: “Behave in a way that makes it easy for people to like you, to want to respect you, and to follow you.” Yes, Reagan, bless his memory, was always a gentleman. But he still got shellacked in the media, just like Trump – who won this voter’s loyalty not by turning the other cheek at media lies but by hitting back twice as hard.

Yes, he’s a very different man from Reagan. So what? The feisty John Adams represented a sea change after the stoic George Washington. And imagine getting used to the earthy, straight-from-the-hip Harry Truman – who threatened to belt a reporter who’d written a negative review of a piano performance by the president’s daughter, Margaret – after twelve years of the patrician FDR.

Before reading Inside the Reagan White House, I didn’t know anything about Lavin. His comments on Trump and January 6 motivated me to look into him a bit further. On his Wikipedia page I discovered that he had endorsed Hillary Clinton in 2016 and Joe Biden in 2020; when he made the latter endorsement he even signed a statement, along with 130 other veteran GOP operatives, to the effect that Trump was unsuited to another term in the White House and that it was therefore “in the best interests of our nation” to elect Biden.

Given that Lavin claims to place so much store by kindness, ethics, inclusivity, and other admirable attributes when deciding which politician to admire, it’s rather rich to find out that he supported Hillary and Joe, those world-class grifters, the former of whom was known for being the surliest First Lady of modern times and the latter of whom, already decrepit four years ago, was a lifelong mediocrity and, throughout his four years in the Oval Office, the unwitting tool of far-left ideologues.

Still, I guess Lavin’s recent voting history isn’t too surprising: he admits in his book that he’s an “establishment man,” by which he apparently means that he’s a swamp creature, more comfortable with other members of that species than with a candidate who puts America first, restored its economy, has kept us out of war, and refuses to take a paycheck. But what a shame that a man who professes to have had so much respect for Reagan – and who even, for heaven’s sake, finds nice things to say about Bill Clinton and Jimmy Carter – should have so little regard for the best president since Reagan.

First published in Front Page Magazine